Alloplastic Augmentation of the Facial Skeleton: An Occasional Adjunct or Alternative to Orthognathic Surgery

Background:

Alloplastic implants can be adjunctive to orthognathic surgery by correcting contour irregularities or disharmonies after skeletal movements. Implant augmentation can also simulate the visual effect of osteotomies in patients with skeletal deficiencies whose occlusion is normal or has been corrected. Although sometimes it is an adjunct or an alternative to facial skeletal rearrangements, facial skeleton augmentation is not a substitute for orthognathic surgery.

Methods:

Alloplastic implants designed specifically to augment the infraorbital rim can correct the residual upper midface deficiency remaining after Le Fort I maxillary advancement. When used with paranasal and malar implants, they can simulate the visual effect of the Le Fort III osteotomy with advancement. Paranasal implants can simulate the appearance after Le Fort I advancement. Mandible and extended chin implants can correct skeletal irregularities and deficiencies after sagittal and horizontal osteotomies. They can also simulate the visual effect of these osteotomies.

Results:

The application of these concepts has been effective, with low morbidity, in 294 patients. No implants extruded or migrated. Eight patients (3 percent) had early postoperative infections. There were no late infections. Ten of 108 patients (9 percent) with midface implants had implant visibility with time.

Conclusion:

Alloplastic augmentation of the facial skeleton can be a useful adjunct or an alternative to orthognathic surgical procedures in situations when the occlusion is normal or has been corrected. (Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 127:2021,2011.)

Facial skeletal disharmony most often manifests as midface or mandibular deficiencies.

When severe, these deficiencies result in malocclusion and are treated with skeletal osteotomy

and rearrangement. Patients with less severe skeletal deficiencies and occlusal abnormality can

have their occlusal relationships improved with orthodontic tooth movement alone. In both patient groups, these treatments may optimize occlusion and, thus, dental function. However, the resulting skeletal contours are often less than ideal. Both treatment groups may benefit from selective augmentation of their facial skeleton with alloplastic implants to normalize skeletal contours and thus improve facial appearance.1-5 Although useful for patients with certain skeletal disharmonies, facial skeletal augmentation is not a substitute for orthognathic surgery.

This article describes the use of alloplastic implants as an occasional adjunct or alternative to orthognathic surgery. It integrates patient examples in the description and application of the concept. It documents the clinical experience of the application of these concepts.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Orthognathic Surgery Adjunct

After Le Fort I Advancement

Midface deficiency associated with significant malocclusion is most often treated with horizontal osteotomy of the maxilla at the Le Fort I level with advancement of the tooth-bearing segment. The standard Le Fort I osteotomy advances only the maxillary alveolus and adjacent skeleton beneath the infraorbital foramen. It does not include the infraorbital rim and malar areas. Patients in whom the infraorbital region was deficient before Le Fort I osteotomy will continue to be deficient post- operatively. The rim deficiency in the parasagittal plane may be accentuated by the more advanced position of the tooth-bearing segment. Cephalometric analysis in preparation for maxillary advancement focuses on the midsagittal plane. Rosen, a visionary in optimizing the aesthetic consequences of orthognathic procedures, argued that consideration of the parasagittal plane can be equally or perhaps more important for facial aesthetics.1’

The postoperative imbalance in midface parasagittal projection may be corrected by alloplastic augmentation of the skeleton above the advanced tooth-bearing segment. This augmentation always includes the infraorbital rim7 and is often used in combination with malar implants (Fig. 1).

After Mandibular Osteotomies

Patients with class II dental malocclusion caused by mandibular deficiency are usually treated by sagittal split osteotomy. This procedure separates the tooth-bearing symphysis and adjacent bodies from the rami. Requisites for positioning the resultant anterior and posterior segments to improve occlusion, allow bone healing, and maintain joint function may result in displeasing postoperative contours and disharmonies. The anterior repositioning of the tooth-bearing segment is dictated by occlusal relations. Its separation from the posterior segment creates an irregularity at the site of the osteotomy. This area of narrowing along the inferior border of the mandible may be visible in certain individuals.

Positioning of the posterior segment requires that its condyle be seated in the glenoid fossa and that there be sufficient contact at the osteotomy site with the occlusal segment to allow bone healing. Thus, the position of the mandibular angle is dictated by the fulfillment of these criteria. Because the position and obliquity of the bilateral osteotomies are never identical, the position of the mandible angles is destined to some degree of asymmetry and unpredictability. This may result in an aesthetically displeasing position of the ramus, resulting in an angle with insufficient height, insufficient width, or asymmetry. Postoperative bone resorption may also contribute to posterior deficiency.

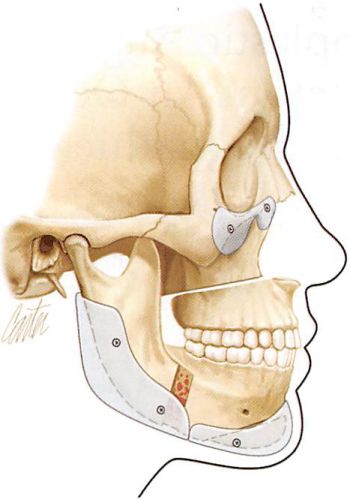

Fig. 1. Artist’s rendition of adjunctive use of alloplastic implants to correct skeletal imbalances and irregularities after orthognathic procedures. An implant designed to augment the infraorbital rim and anterior malar area corrects the upper midface deficiency after Le Fort I osteotomy and advancement. An implant placed in the posterior mandible smooths the area of narrowing along the inferior border at the sagittal osteotomy site and restores angle projection and ramus height. The extended chin implant, in this case, corrects the step deformity after horizontal osteotomy and adds chin projection.

Horizontal osteotomy of the chin with advancement of the inferior segment (sliding genioplasty) is often performed in conjunction with the sagittal split osteotomies. Unless the horizontal osteotomy is carried well posterior to the mental foramen, a contour irregularity at the site of the osteotomy may be visible. The notching or indentation is especially detrimental to those who have a preexisting prejowl sulcus.

Alloplastic implants are available to camouflage contour irregularities and asymmetries that occur after mandibular osteotomies. Alloplastic augmentation of the posterior mandible may increase posterior width, increase ramus height, decrease inclination of the mandibular border, and correct inferior border irregularities at the sagittal osteotomy sites. Extended chin implants can be used to correct indentations and lessen asymmetries after horizontal osteotomies (Fig. 1).

Orthognathic Surgery Alternative

Midface and mandibular hypoplasia are common facial skeletal variants. In patients with these morphologies, occlusion can be normal or can be compensated by orthodontics. Orthodontic tooth movements to obtain occlusion have been reported to be applicable for correction of up to 8 mm for positive overjet, 4 mm for negative overjet, and 3 mm for transverse width discrepancy.8 In skeletally deficient patients whose occlusion is normal or has been previously normalized by orthodontics, skeletal repositioning would necessitate additional orthodontic tooth movement. Such a treatment plan is time consuming and costly. It introduces many morbidities associated with skeletal osteotomies including the contour irregularities noted above, possible relapse, and sensory nerve injury.9 It is therefore appealing to few patients. In these patients, the appearance of skeletal osteotomies and rearrangements can be simulated through the use of facial implants.10 Diagrammatic representations of how implant surgery can mimic the appearance of skeletal osteotomies in patients with normal or corrected occlusion are shown in Figures 2 through 4. Augmentation of the pyriform aperture area can simulate the visual effect of Le Fort I osteotomy with advancement3 (Fig. 2). The use of multiple midface implants including those that augment the infraorbital rim and the malar and pyriform areas can simulate the visual appearance of Le Fort III osteotomy and advancement-(Fig. 3). Combinations of mandible and chin implants can simulate the appearance of sagittal and horizontal osteotomies with advancement11 (Fig. 4).

Preoperative Evaluation

Because occlusion is satisfactory or has been corrected in these patient groups, skeletal augmentation is determined by the aesthetic concerns of the patient. Physical examinations together with standardized photographs are paramount in analysis and surgical planning. Plain radiographs and, particularly, computed tomographic scans with three- dimensional reconstruction can be useful adjuncts. In certain instances, particularly those patients with significant asymmetries, models obtained from computed tomographic data add the physical dimension to the planning and have been used to manufacture customized implants.

Overview of Operative Technique

A general anesthetic is preferred. This approach protects the airway during the operation and allows optimal intraoral preparation and surgical access to the midface and mandible.

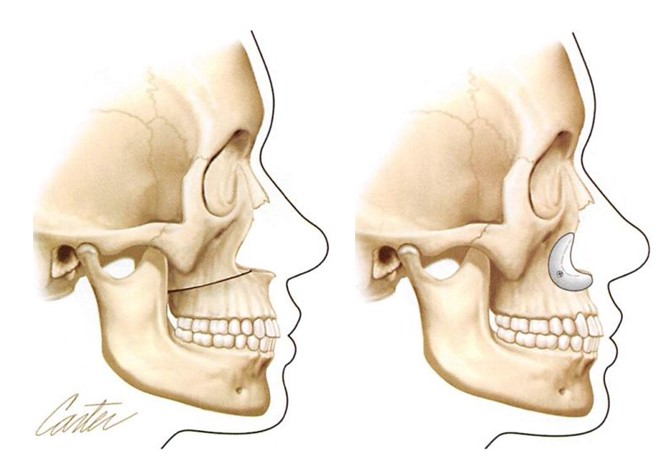

Fig. 2. Diagrams show how implant augmentation of the lower midface (pyriform aperture) can simulate the visual appearance of Le Fort I osteotomy and advancement without altering dental occlusion. (Left) Illustration of lower midface concavity with class III malocclusion corrected by Le Fort I osteotomy with advancement. (Right) Lower midface implants provide the visual effect of Le Fort I osteotomy and advancement but do not alter occlusion.

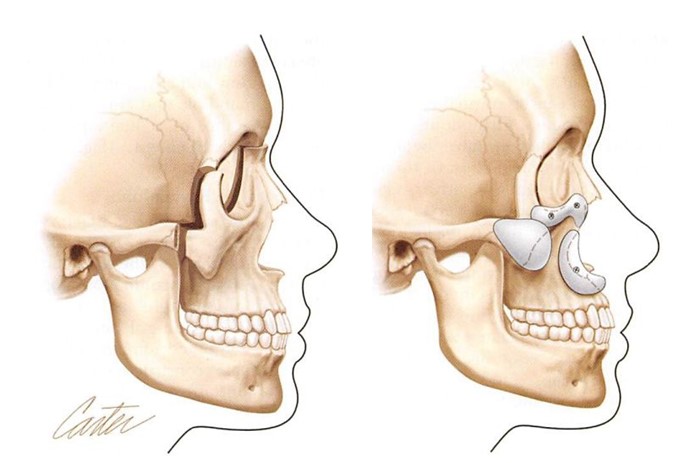

Fig. 3. Diagrams showing how multiple implant augmentation of the upper and lower midface skeleton can simulate the visual appearance of Le Fort III osteotomy and advancement without altering dental occlusion. {Left) Illustration of midface concavity and class III malocclusion corrected by Le Fort III osteotomy with advancement. (Right) Multiple midface implants provide the visual effect of Le Fort III osteotomy and advancement but do not alter occlusion.

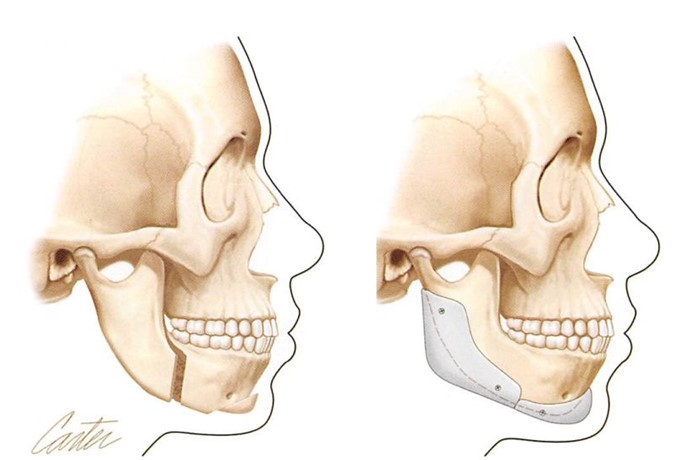

Fig. 4. Diagrams showing how implant augmentation of the mandible can simulate the visual appearance of sagittal and horizontal osteotomies of the mandible without altering dental occlusion. (Left) Mandibular deficiency with class II occlusion corrected by sagittal and horizontal osteotomies of the mandible. Note that the occlusion has been corrected from class II to class I. (Right) In the patient with mandibular deficiency and class I occlusion, the visual effect of sagittal and horizontal osteotomies with advancement has been simulated with mandible and chin implants. Note that the class I occlusion is unchanged. Notice also that the border regularities inherent in skeletal osteotomies are avoided when implants are used.

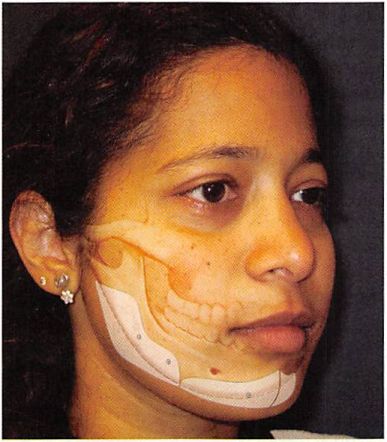

Fig. 5. A 35-year-old woman had undergone Le Fort I maxillary advancement and sagittal and horizontal mandibular osteotomies. Infraorbital rim augmentation and subperiosteal midface elevation was performed to improve midface aesthetics. Infraorbital rim augmentation and midface resuspension has elevated the cheek prominence, resulting in an improved lid cheek interface, with resultant short lid and full cheek. Mandible implants were placed to increase posterior width and increase angle definition. An extended chin implant improved the anterior border contour. (Above) Preoperative and postoperative frontal views. (Center) Preoperative and postoperative lateral views. (Below) The artist has drawn the underlying skeleton and implant applications.

To optimize hemostasis, a dilute epinephrine solution is infiltrated in the operative site. Intraoral sulcus incisions are used to access the midface for placement of paranasal and malar implants. Infraorbital rim augmentation requires periorbital (lower blepharoplasty) incisions. The posterior mandible is accessed through intraoral sulcus incisions, and it is the authors’ preference to access the chin from a submental approach.

The area to be augmented is widely exposed in the subperiosteal plane. Implants are modified as necessary to meet the specific needs of the patient. It is the author’s preference to use porous polyethylene implants fixed with titanium screws. Screw fixation prevents implant movement, allows the implant to be contoured in place, and obliterates gaps between the posterior surface of the implant and the anterior surface of the skeleton. Gaps result in unanticipated increases in implant projection and thus skeletal contour.1-3,7,11

Suction drains are routinely used. Chlorhexidine gluconate mouthwashes are prescribed for use 3 days postoperatively. Intravenous antibiotics are administered perioperatively. Oral antibiotics are prescribed for 1 week after surgery.

RESULTS

This concept has been used in 294 patients (203 female patients and 91 male patients) over an 8-year period. The average age was 34 years (range, 17 to 68 years). Sixty had implant surgery as an adjunct to previously performed orthognathic surgery, and 234 patients had implant surgery as an alternative to orthognathic surgery. No implants extruded or migrated. Ten of 108 patients (9 percent) with midface implants had visibility with time, reflecting the fact that soft tissues change over time whereas implants do not lose their projection.

Eight patients (3 percent) had postoperative infections. Two of these eight patients had a history of previous implant-related infections treated unsuccessfully with months-long courses of antibiotics. One of these patients was human immunodeficiency virus-positive. Another patient had previously undergone radical neck dissection and radiation therapy. Three patients presenting with infection during the first postoperative week were treated successfully with repeated irrigations and intravenous antibiotics. The other four patients presented 3 to 4 weeks after surgery and were treated with implant removal. One of the patients (human immunodeficiency virus-positive) successfully treated within the first week presented 2 years after surgery with an orbital cellulitis.

Fig. 6. A 26-year-old woman had undergone sagittal split and horizontal osteotomies of the mandible to correct mandibular deficiency with class II malocclusion. Contour deficiencies and irregularities, including deficient gonial angles, were improved with mandible and chin implants. The vertical height of the chin was reduced by contouring at its inferior border. (Above and center) Pre-operative and postoperative (1 year) oblique views. (Below) The artist has drawn the underlying skeleton and implant applications.

His implant was removed to eliminate it as a possible septic focus. No purulence was found and results of wound cultures were negative for bacterial growth.

No other patient presented with a late infection that could be related to the implant. Patients who have had implant surgery as an adjunct or alternative to orthognathic surgery are presented in Figures 5 through 9.

DISCUSSION

Rosen, in multiple writings,6,12-14 was one of the first to point out aesthetic inadequacies that may accompany adherence to classic skeletal movements based on cephalometric data. He emphasized that when given alternatives to satisfy occlusal inadequacies it is usually better to expand rather than to reduce the facial skeleton. This skeletal expansion provides support for, and allows better drape of, the soft-tissue mask with, as he demonstrated, a more youthful and attractive appearance.

The use of alloplastic implants as an adjunct to previously performed orthognathic procedures or as a simulation of skeletal advancements in patients with normal or orthodontically corrected occlusion inevitably expands the skeleton. As advocated by Rosen, it adds to midface convexity or mandibular border and angle definition with their attendant aesthetic benefits.

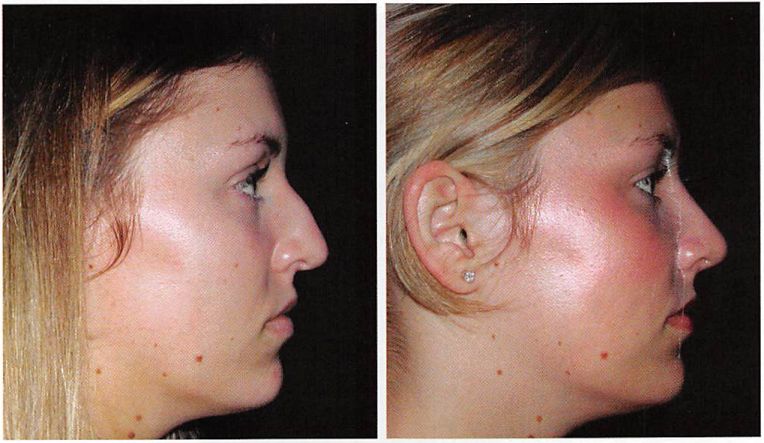

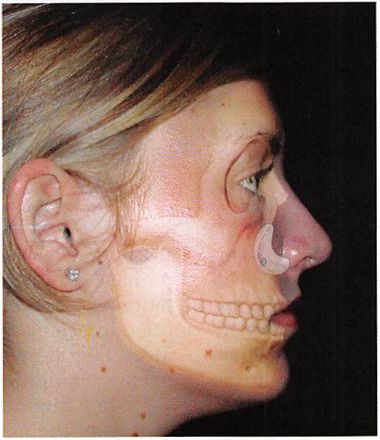

Fig. 7. A 22-year-old woman with lower midface deficiency and normal occlusion underwent paranasal augmentation at the time of aesthetic rhinoplasty. Note the increase in lower midface projection simulating the appearance of Le Fort I osteotomy with advancement. (Above) Preoperative and postoperative (1 year) lateral views. (Below) The artist has drawn the underlying skeleton and implant applications.

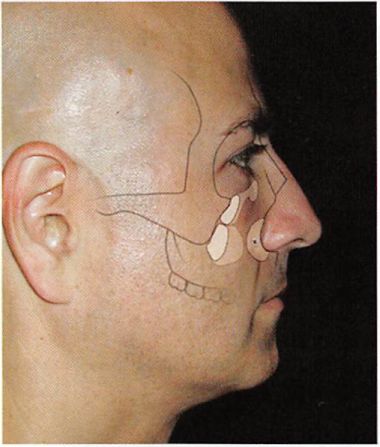

Fig. 8. A 32-year-old man with midface deficiency and corrected occlusion underwent midface augmentation with infraorbital rim, paranasal, and malar implants. (Above) Preoperative and postoperative (1 year) lateral views. (Below) The artist has drawn the underlying skeleton and implant applications.

Contour irregularities and deficiencies after orthognathic procedures in the midface have been noted and addressed by others.115 This has largely been confined to the midface after Le Fort osteotomy. Nocini et al. have designed a midfacial zonal analysis to identify and address deficiencies in the midface with implants at the time of jaw surgery.5

Malar deficiency has been most often addressed with implants at the time of orthognathic surgery or during a second procedure. It is the author’s contention that malar augmentation alone as an adjunct may introduce yet another imbalance. Malar augmentation usually widens the midface, which tends to exaggerate the upper midface concavity. Thus, infraorbital rim augmentation is considered the critical element in creating midface balance after Le Fort I advancement. More lateral malar augmentation may be an appropriate adjunct.

When augmenting both the upper and lower aspects of the midfacial skeleton to simulate a Le Fort III advancement, multiple implants rather than a single large implant are preferred. A single large midface implant is unlikely to adapt to the underlying curvatures of the native skeleton. Large gaps between the posterior surface of the implant and the anterior surface of the skeleton result.

Fig.9. A 32-year-old woman with mandibulardeficiency and corrected occlusion underwentchin and mandible implant augmentation. [Above) Preoperative and postoperative (2 years) oblique views. (Below) The artist has drawn the underlying skeleton and implant applications.

These gaps result in unanticipated increases in implant projection (implant thickness + gap = effective implant projection). The facial contours lose their innate shape and take on an “implant face†appearance.

Both the soft tissues and the skeleton contribute to midface contour and convexity. Thus, both soft-tissue and skeletal augmentation can be appropriate for creating midface convexity. However, these modalities are not equivalent in their impact on the appearance of the midface. Free fat grafting and the injection of various fillers is intuitive and appropriate for the restoration of soft-tissue volume loss caused by senile atrophy. It has a limited role in simulating the effect of an increase in skeletal projection. Whereas augmenting the facial skeleton results in an increase in the projection of the skeleton, augmenting the soft- tissue volume results in an inflation of the soft- tissue envelope and blunting of the contours of the skeleton. Over augmentation of either component brings home the point. If overly large implants were placed on the skeleton, the appearance would be too defined and, ultimately, skeletal. If too much fat or filler were placed in the soft-tissue envelope, an increasingly spherical and otherwise undefined shape would result. A similar situation arises when soft-tissue augmentation is performed to simulate the appearance of significant chin or mandible augmentation.

Soft-tissue volume augmentation has been complementary16,17 to both the adjunctive and alternative use of alloplastic implants to orthognathic procedures. Because soft tissues change over time and implants do not, soft-tissue augmentation can mask implant visibility in patients with senescence-attenuated soft-tissue envelopes. When patients are both skeletal and soft-tissue deficient, the use of both modalities can optimize the result.

CONCLUSIONS

Alloplastic augmentation of the facial skeleton can be a useful adjunct or an alternative to orthognathic surgical procedures in situations when the occlusion is normal or has been corrected. Alloplastic implants can improve contour irregularities left after skeletal movements. In patients with acceptable occlusion, their use can simulate the visual effect of skeletal movements.

Michael J. Yaremchuk, M.D.

Massachusetts General Hospital Boston, Mass. 02114

PATIENT CONSENT Patients provided written consent for the use of their images.

REFERENCES

1. Yaremchuk MJ, Chen YC. Enlarging the deficient mandible. Aesthet SurgJ. 2007;27:539-550.

2. Yaremchuk MJ. Making concave laces convex. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2005;29:141-147; discussion 148.

3. Yaremchuk MJ, Israeli D. Paranasal implants for correction of midface concavity. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1998;102:1676- 1684; discussion 1685.

4. Robiony M, Costa F, Demitri V, Politi M. Simultaneous ma- laroplasty with porous polyethylene implants and orthognathic surgery for correction of malar deficiency. J Oral Max- illofac Surg. 1998;56:734-741; discussion 742.

5. Nocini PF, Boccieri A, Bertossi D. Gridplan midfacial analysis for alloplastic implants at the time of jaw surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;123:670-679.

6. Rosen I4M. Aesthetic Perspectives in Jaw Surgery. New York: Springer; 1999.

7. Yaremchuk MJ. Infraorbital rim augmentation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;107:1585-1592; discussion 1593-1595.

8. Squire D, Best AM, Lindauer SJ, Laskin DM. Determining the limits of orthodontic treatment of overbite, oveijet, and transverse discrepancy: A pilot study. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2006; 129:804—808.

9. Morris DE, Lo LJ, Margulis A. Pitfalls in orthognathic surgery: Avoidance and management of complications. Clin Plast Surg. 2007;34:e 17-e29.

10. Yaremchuk MJ. Indications, evaluation and planning. In: Yaremchuk MJ. Atlas of Facial Implants. Philadelphia: Saun- ders-Elsevier; 2007:3-22.

11. Yaremchuk MJ. Mandibular augmentation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000;106:697-706.

12. Rosen HM. Occlusal plane rotation: Aesthetic enhancement in mandibular micrognathia. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1993;91: 1231-1240; discussion 1241-1244.

13. Rosen HM. Facial skeletal expansion: Treatment strategies and rationale. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1992;89:798-808.

14. Selber JG, Rosen HM. Aesthetics of facial skeletal surgery. Clin Plast Surg. 2007;34:437-445.

15. Carboni A, Cerulli G, Perugini M, Renzi G, Becelli R. Longterm follow-up of 105 porous polyethylene implants used to correct facial deformity. Eur J Plast Surg. 2002;25:310-314.

16. Reiche-Fischel O, Wolford LM, Pitta M. Facial contour reconstruction using an autologous free fat graft: A case report with 18-year follow-up./Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2000; 58:103-106.

17. Ellenbogen R, Motykie G.Youn A, Svehlak S, Yamini D. Facial reshaping using less invasive methods. Aesthet Surg ]. 2005; 25:144-152.

2030