Anatomical Landmarks to Avoid Injury to the Great Auricular Nerve During Rhytidectomy

Abstract

Background: An estimated 116 086 facelifts were performed in 2011. Regardless of the technique employed, facial flap elevation carries with it anatomical pitfalls of which any surgeon performing these procedures should be aware. Injury to the great auricular nerve (GAN) is the most common of these injuries, occurring at a rate of 6% to 7%.

Objectives: We report our findings on the location of the GAN on the basis of anatomical landmarks to aid surgeons with planning their surgical approach for safe elevation of rhytidectomy skin flaps in the lateral neck region.

Methods: Sixteen fresh cadaveric heads were dissected under loupe magnification. All specimens were dissected in a 45-degree (facelift) position in which a mid-sternocleidomastoid (SCM) incision was used for exposure. Measurements from the bony mastoid process, bony external auditory canal, external jugular vein, and anterior border of the SCM to the GAN were taken in each cadaver.

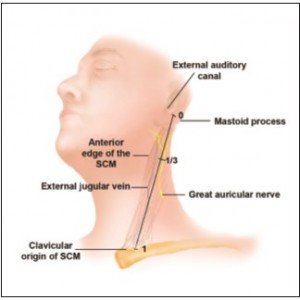

Results: The GAN follows a consistent course over the mid-body of the SCM before bifurcating into anterior and posterior branches and terminal arborization. Regardless of the length of the SCM, the GAN at its most superficial location was found to be consistently at a ratio of one-third the distance from either the mastoid process or the external auditory canal to the clavicular origin of the SCM.

Conclusions: Knowledge of the anatomy, course, and location of the GAN along the surface of SCM muscle based on anatomic landmarks and distance ratios can facilitate a safer dissection in the lateral neck during rhytidectomy procedures.

Keywords facelift, rhytidectomy, nerve damage, great auricular nerve, anatomic landmarks, SMAS

Accepted for publication June 12, 2012.

An estimated 116 086 facelifts were performed in 2011.1 Despite previous descriptions of nerve location, the great auricular nerve (GAN) is still the most commonly injured nerve in facelift procedures. A review of the literature suggests a GAN complication rate of 6% to 7%.2-4 Sequelae of GAN injury can range from pure anesthesia to parasthesias and even painful neuromas in the distribution of the nerve. Permanent numbness has been cited in up to 5% of patients in a single series.2-8 Patients have documented trouble with wearing earrings, using the telephone, shaving, and combing their hair.6,7 Although certainly not as catastrophic as a facial nerve injury, this complication can present as a functional impairment and nuisance to the patient and surgeon alike.

Anatomically, the GAN is protected as it courses behind the sternocleidomastoid (SCM). Once it emerges onto the anterior surface of the muscle, it resides in a superficial plane, making it vulnerable to injury, particularly if the surgeon is elevating facial flaps and inadvertently entering the superficial fascia of the SCM.2-5 Articles by McKinney and Katrana,2 Izquierdo et al,4 and Sand and Becser8 have defined absolute measurements that can be used to predict the location of the GAN, but these estimates can vary greatly depending on the size and body habitus of individual patients.

The aim of this article is to more accurately predict the location of the GAN at its most superficial location (where it is most vulnerable to injury) while taking into account the variations in patient size and body habitus that surgeons encounter. This can be achieved by determining distance ratios based on clear and reproducible anatomic landmarks.

Methods

Sixteen fresh cadaveric face and neck halves were dissected with the aid of 2.5 loupe magnification to determine the 3-dimensional location of the GAN as it superficially coursed over the SCM. The specimen group consisted of 9 males and 7 females. None of the specimens had any signs of previous trauma or surgical scars in the head and neck region. The ages of the cadavers were unknown.

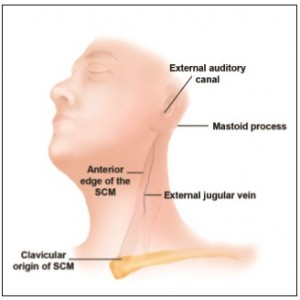

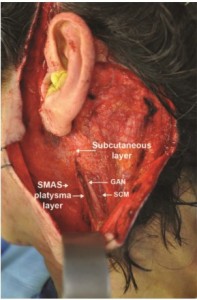

All dissections were performed in a 45-degree position (facelift position) with a mid-SCM incision for maximal exposure. Skin flaps were elevated, and full exposure of the SCM as well as the GAN and its branches was noted. Measurements were taken from multiple bony and soft tissue landmarks to the GAN. Landmarks were chosen based on easily identifiable structures that could be noted preoperatively and intraoperatively (Figure 1).

The distances from the GAN to the mastoid process, the external jugular vein, the bony external auditory canal, and the anterior SCM were measured. Subsequently, the GAN and its relation to the SCM in its most superficial plane was determined as a distance ratio in order for the surgeon to correct for size and anatomical differences between patients. Statistical data were calculated as the average measurement from the bony external auditory canal to the GAN and its relation to the SCM in its most superficial plane (average ± standard deviation). In addition, the average length of the SCM was calculated in relation to the SCM in its most superficial plane and reported as a distance ratio.

Results

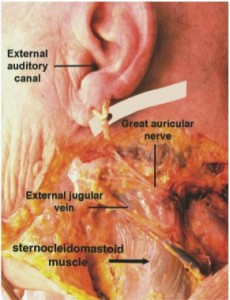

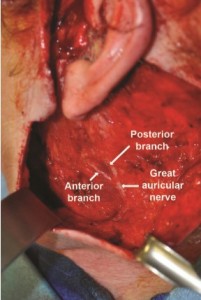

In all 16 dissections, the GAN was found to consistently course over the mid-body of the SCM before bifurcating into anterior and posterior branches and terminal arborization (Figures 2-3). The most superficial location of the GAN was found on the mid-portion of the SCM, approximately 1 cm from the external jugular vein.

The range of distances from the GAN at this superficial location to the mastoid process and the bony external auditory canal was 5.8 to 7.4 cm, with an average distance of 6.5 ± 0.9 cm. The average length of the SCM in the specimen group was 19.3 cm, with a great deal of variation between cadavers (18-21.5 cm). Despite this noted variability between specimen size and anatomical variability, the GAN was found to be one-third the distance from either the mastoid process or the external auditory canal to the clavicular origin of the SCM. In other words, the ratio of 6.5 cm to 19.3 cm is 0.337, which is approximately one-third (Figure 4). In addition, the distance ratio for each specimen ranged from 0.32 to 0.35 (average, 0.33), with no difference between males and females.

Discussion

The anatomy of the great auricular nerve has been extensively studied and documented over the past 30 years. The GAN is a purely sensory nerve that arises from C2 and C3 spinal roots to fuse into the main trunk before emerging onto the mid-body of the SCM muscle, where it resides in its most superficial location before bifurcating into anterior and posterior branches. The anterior branch continues in a plane between the SCM and the parotid gland prior to its terminal arborization, providing sensation to the skin overlying the parotid gland and anteroinferior aspect of the auricle. The posterior branch travels on the surface of the SCM before reaching the mastoid area and terminating in the postauricular area to give sensation to the posteriorinferior aspect of the auricle.

Attempts to accurately delineate the course and location of the GAN have, thus far, relied mostly on the bony external auditory canal and the superficial musculoaponeurotic system (SMAS).2 McKinney and Katrana2 noted the relationship of the GAN to the SCM, SMAS, and platysma with regard to the vulnerability of the nerve as the thin SMAS layer blends with the superficial investing fascia of the SCM. In their dissection of 7 cadavers, they noted consistency in the location of the nerve crossing the midtransverse belly of the SCM at a point 6.5 cm below the caudal edge of the bony external auditory meatus.

As rhytidectomy techniques were popularized and increasingly more reliant on SMAS-platysma dissections, the relationship of the GAN to the SMAS layer ignited additional interest in the anatomy of the GAN. McKinney and Katrana2 concluded that incision and elevation of the SMAS parallel to the anterior border of the SCM would not result in inadvertent injury to the GAN. Moreover, plication sutures could be placed more safely when the location of the nerve trunk was known. Izquierdo et al4 revisited the anatomy of the GAN and demonstrated variability with respect to McKinney’s previously described point. This may have been due to the differences in skin laxity, size, and body habitus of the specimens used in the studies. When elevating a skin flap in the postauricular region, it is recommended to stay within the subcutaneous layer, particularly when dissection proceeds anteriorly over thebelly SCM muscle. The GAN is deep to the SCM investing fascia, which is deep to the overlying SMAS layer. It is more risky to elevate a SMAS layer over the SCM because of the adherent nature of the SMAS to the SCM fascia. Raising a SMAS-platysmal flap medial to the anterior border of the SCM should not endanger the GAN, as the nerve is deep enough to allow safe elevation. This was noted already by McKinney and Gottlieb3 in a 1985 follow-up study, as well as in our clinical experience (Figure 5).

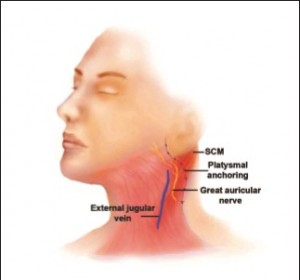

In addition to the risk of incising the SMAS-platysma layer in proximity to the GAN, flap anchoring and plication to the mastoid process can endanger the posterior branch of the GAN. Izquierdo et al4 suggested that performing suture plication of the flap posterior to a line drawn from McKinney’s point to a point 1.5 cm posterior to the lobule and parallel to the Frankfort plane could prevent such injuries (Figure 6).

In addition to the bony landmarks, the external jugular vein (EJV) can be used as a landmark for the location of the GAN. The distance between the EJV and the GAN is 5 to 10 mm.2,9 The nerve is noted emerging from the posterior border the SCM and traversing the plane of dissection in parallel to and along the middle and upper third of the vein. Therefore, when identifying the EJV in the subplatysmal plane, the predicted location of the GAN is approximately 1 cm superior and lateral to the EJV, coursing in a trajectory parallel to the vein (Figures 2 and 4).

Sand and Becser8 found great variability in the course of the GAN at its “exit†point onto the SCM and along its path of ascent on the muscle. The dissected GAN entered the superficial layer between 5.5 and 10.5 cm from external auditory meatus (the median of 6.8 cm corresponds to McKinney’s point). In addition, variability was identified in the postauricular ascent of the nerve. It was located in the recess between the helix and the skull (n = 6), in the subcutaneous layer over the mastoid process (n = 5), or at the posterior auricular surface in 2 of the specimens. Another anatomic study defined the location of the GAN in relationship to the fat compartments of the head and neck. Rohrich et al10 identified 5 periauricular adipose compartments. The main branch of the great auricular nerve always ran within the subauricular membrane. The subauricular membrane was located between the subauricular and inferior adipose compartments. In this cadaveric study, McKinney’s point was consistently found to lie where the great auricular nerve travels deep to the inferior border of Lore’s fascia and the tail of the parotid. Below this point, the great auricular nerve is closer to the skin surface and more susceptible to potential injury. To our knowledge, this study is the first attempt to describe a distance ratio for the location of the GAN with the use of easily identifiable bony landmarks to accommodate for differences in patient size, skin laxity, and overall body habitus. Although techniques in rhytidectomy continue to change and evolve, the knowledge of these anatomic ratios can help surgeons navigate safely in the lateral neck and avoid the sequelae of GAN injury.

Conclusions

The GAN is found at its most superficial location approximately one-third the distance from the external auditory canal to the clavicular origin of the SCM. A similar distance ratio exists from the mastoid process to the clavicular origin of the SCM. With these bony anatomic landmarks, the surgeon can accurately predict the location of the GAN at it most vulnerable site and reliably proceed with flap dissection in the lateral neck during rhytidectomy procedures.

Disclosures

The authors declared no conflicts of interest with respect to the authorship and publication of this article.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research and authorship of this article.

References

- American Society for Aesthetic Plastic Surgery National Cosmetic Surgery Databank Statistics. http://www.surgery.org/media/statistics. Accessed June 8, 2012.

- McKinney P, Katrana DJ. Prevention of injury to the great auricular nerve during rhytidectomy. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1980;66(5):675-679.

- McKinney P, Gottlieb J. The relationship of the great auricular nerve to the superficial musculoaponeurotic system. Ann Plast Surg. 1985;14(4):310-314.

- Izquierdo R, Parry SW, Boydell CL, Almand J. The great auricular nerve revisited: pertinent anatomy for SMASplatysma rhytidectomy. Ann Plast Surg. 1991;27(1): 44-48.

- de Chalain T, Nahai F. Amputation neuromas of the great auricular nerve after rhytidectomy. Ann Plast Surg. 1995;35(3):297-299.

- Patel N, Har-El G, Rosenfeld R. Quality of life after great auricular nerve sacrifice during parotidectomy. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2001;127(7):884-888.

- Ryan WR, Fee WE Jr. Great auricular nerve morbidity after nerve sacrifice during parotidectomy. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006;132(6):642-649.

- Sand T, Becser N. Neurophysiological and anatomical variability of the greater auricular nerve. Acta Neurol Scand. 1998;98(5):333-339.

- Murphy R, Dziegielewski P, O’Connell D, Seikaly H, Ansari K. The great auricular nerve: an anatomic and surgical study. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2012;41(suppl 1):S75-S77.

- Rohrich RJ, Taylor NS, Ahmad J, Lu A, Pessa JE. Great auricular nerve injury, the “subauricular band†phenomenon, and the periauricular adipose compartments. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;127(2):835-843.

Leave Comments

You must be logged in to post a comment.