Changes in Eyebrow Position and Shape with Aging

Background:

Lack of an objective goal for brow-lift surgery may explain why several articles in the plastic surgery literature conclude that brow lifts produce eyebrows with shape and position that are not aesthetically pleasing. By comparing eyebrow shape and position in both young and mature women, this study provides objective data with which to plan forehead rejuvenating procedures.

Methods:

Two cohorts of women aged 20 to 30 years and 50 to 60 years were photographed to determine eyebrow position. Measurements were made from a horizontal plane between the medial canthi to three points at the upper eyebrow margin. Exclusion criteria included prior surgery, plucked eyebrows, and botulinum toxin.

Results:

The eyebrow in the 20- to 30-year-old group (n = 36) was 15.7, 19.8, and 21.3 mm above the medial canthus, pupil, and lateral canthus, respectively. Lateral brow position was significantly higher than the mid brow (p < 0.05). In the 50- to 60-year-old group (n = 34), the brow was 19.1, 22.4, and 22.4 mm above the medial canthus, pupil, and lateral canthus, respectively. At all three points, the brow was higher in older compared with younger subjects. This difference was significant at the medial and mid brow (p < 0.05).

Conclusions:

Unlike other areas of the body where there is descent of soft tissues, there is paradoxical elevation of eyebrows with aging. These findings explain why surgical elevation of the mid and medial brow provides results that are neither youthful nor aesthetically pleasing. Techniques that selectively elevate the lateral brow are more likely to have a rejuvenating effect on the upper third of the female face. (Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 124: 1296, 2009.)

To achieve consistent surgical outcomes with eyebrow rejuvenating procedures, aesthetic objectives for youthful brow shape and position need to be defined. In 1974, Westmore described characteristics of the ideal eyebrow as an arch where the brow apex terminates above the lateral limbus of the iris, with the medial and lateral ends of the brow at the same horizontal level.1

Freund and Nolan surveyed plastic surgeons and cosmetologists about their preferences for both

eyebrow height and shape. Both groups preferred a medial eyebrow below or at the supraorbital rim with a shape that has an apex lateral slant.2 Definitions of eyebrow aesthetics have been refined further by others, but considered together they provide a framework of aesthetic goals for surgeons to plan forehead rejuvenating procedures.3

From I he Division of Plastic Surgery, Department of Surgery, Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Received for publication February 3, 2009; accepted April 20, 2009.

Presented at the 88th Annual Meeting of the American Association of Plastic Surgeons, in Rancho Mirage, California, March 21 through 24, 2009.

Copyright ©2009 by the American Society of Plastic Surgeons

DOI: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181b455e8

Despite studies that provide criteria for ideal brow aesthetics, reports in the literature suggest that brow-lift procedures create brows with unnatural shape and position. The disparity between practice and the ideal was documented in the second part of the study by Freund and Nolan.2 The authors showed that brow lifts pictured in the medical literature frequently elevated medial eye-brows too high to a level above the supraorbital rim. With regard to brow shape, brow-lift surge 17 was significantly more likely to create an apex medial or flat appearance than the desired apex lateral eyebrow contour. Gunter and Antrobus were concerned that the postoperative brow was overelevated, creating a surprised and unintelligent look.4 Through computer image manipulation, the authors demonstrated that the preferred brow was one in which the original position was not elevated but rather reshaped to a more gentle arch. They concluded that surgical brow lifts fail to provide the desired result because they tend to elevate the entire brow without lowering the medial segment. Troilius documented that brow-lift procedures were creating unnaturally high brows by examining postoperative measurements of patients who underwent subperiosteal brow lifts with fixation.5-6 He measured that brows continued to elevate an additional 2.5 mm between 1 and 5 years postoperatively. To achieve more natural results, the author revised his technique to eliminate fixation except in the most severe cases of brow ptosis. At the time, these studies advanced understanding of brow aesthetics by demonstrating pitfalls of current surgical techniques, yet reports thereafter continued to define technical success of forehead rejuvenating procedures by the ability to the elevate brows with durable results.7,8

The belief that forehead surgery creates brows with unnatural shape and height is substantiated by the fact that patients undergo brow-lift reversal. Yaremchuk et al. described a technique to restore brow appearance in 22 patients who underwent prior open or endoscopic brow-lift procedures.9 Patient complaints included high brows with unnatural shape and an increased spread between the medial brows. Through galea scoring, posterior scalp flap advancement, and anchor suture fixation, brows were lowered on average 5 mm relative to an intercanthal line. With this technique, the brow could be repositioned according to patient preference, usually to an apex lateral configuration.

There is no clear explanation for the discrepancy between surgical results and a youthful brow appearance; however, one possibility is that little is understood about the aging process that occurs at the eyebrow. Although anthropometric values in Caucasian women aged 19 to 25 years were recorded by Farkas et al., objective documentation of changes in eyebrow height and shape with age are lacking.10 The majority of the scientific literature on eyebrow height documents only postsurgical change. To our knowledge, there are only two reports describing changes in female brow height through time. Measured at a single point above the pupil, van den Bosch et al. found that the mid brow elevates with advancing age in large cohort of men and women.11 Lambros studied aging of the brow by comparing longitudinal photographs of individuals across 10 to 50 years. Using digital animation, he observed that brows descended in 29 percent of patients and remained stable or elevated in the remainder.12 Improved understanding of the temporal changes that occur in brow position and shape may lead to better technique and outcomes.

In this article, we describe changes in eyebrow position and shape that occur over time by comparing cohorts of women aged 20 to 30 years and 50 to (50 years. The intent is to better understand the aging process of the brow with a reevaluation of current surgical techniques in light of these findings.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

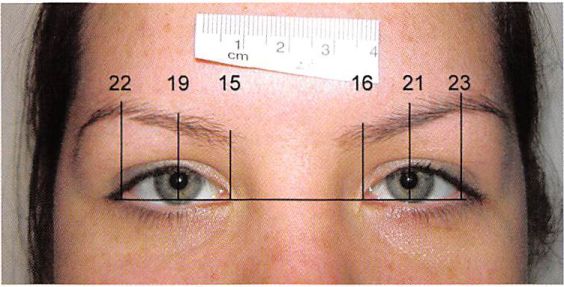

Two random cohorts of Caucasian women aged 20 to 30 years and 50 to 60 years were prospectively photographed for the purpose of this study with the head in the upright position and the neck in neutral position. Digital photographs were captured with the forehead and eyebrows in a maximally relaxed position with the eyes open. To assist brow and frontalis relaxation, patients were asked to close their eyes and then gently open them before being photographed. All images included a metric ruler taped to the mid forehead above the brows. Each eyebrow position was de-termined by measuring from a reference horizontal plane drawn between the medial canthi to vertical points on the upper brow margin at the medial canthus, pupil, and lateral canthus. Using Adobe imaging software (San Jose, Calif.) the photographed metric ruler was manipulated on screen to exactly measure these distances. An example of the methodology, including sample mea-surements, is shown in Figure 1. Women were excluded if they had previous periorbital/forehead surgery, plucked the upper but not lower eyebrow margin, had significant ophthalmologic or neurologic disease, or used botulinum toxin. All measurements were performed twice, once by two authors (E.M. and J.A.G.), to ensure interrater reliability. Statistical analysis was performed by comparing group means with the independent t test using standard statistical software, Intercooled Stata 6.0 (Stata Corp., College Station, Texas). For intragroup comparisons, the paired I test was used. Values of p ^ 0.05 were considered significant.

Fig. 1. Sample of method for determining eyebrow height. A horizontal plane is drawn through the medial canthi. Vertical lines are drawn from the horizontal to the upper brow margin at the medial canthus, pupil, and lateral canthus. The imaged ruler is manipulated on screen to measure vertical heights.

RESULTS

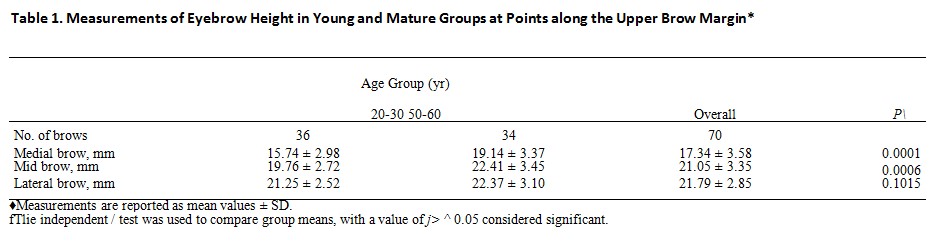

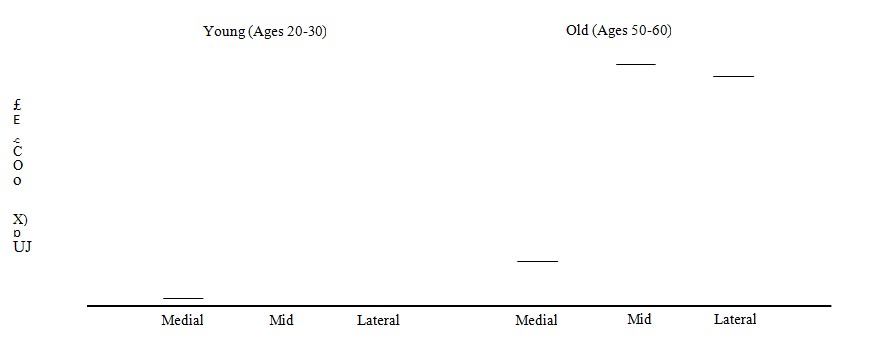

As shown in Table 1, the position of the upper eyebrow margin in the 20- to 30-year-old group (n = 36) was 15.7, 19.8, and 21.3 mm above the medial canthus, pupil, and lateral canthus, respectively. The lateral brow position was significantly higher than the mid brow (/; < 0.05). In the 50- to 60-year-old group (n = 34), the upper brow was 19.1, 22.4, and 22.4 mm above the medial canthus, pupil, and lateral canthus, respectively (Table 1). For each of the three points measured, the brow was at a higher position in the older subjects than in the younger subjects (Fig. 2). This difference was statistically significant at the medial and midbrow positions (/; < 0.05). Typical results for patients from each cohort are shown in Figure 3.

DISCUSSION

Based on what is known about the aging process in other soft-tissue structures of the body, it is logical to believe that eyebrows descend over time. On the contrary, there is evidence in the literature supporting current findings that brows elevate with age. Van den Bosch etal., in an effort to better understand age-related eyelid disease such as ectropion and dermatochalasis, studied the effects of aging on the eyelid, eyeball, and eyebrow.11 In a cross-sectional cohort study of 320 subjects, which included men and women aged 10 to 89 years, the authors determined that eyebrow height over the pupil increased significantly with advanced age in both genders. Eyebrow position was higher overall in women than in men. In contrast, a study by Goldstein and Katowitz of 222 male subjects demonstrated that eyebrow position above the pupil and lateral canthus did not increase but remained the same over time.13 Lam- bros evaluated longitudinal effects of aging at individuals’ brows by overlay of patients’ photographs that spanned an average of 25 years. Using digital animation, it was subjectively observed with-out measurement that brow position elevated in 28 percent, remained stable in 41 percent, and descended in 29 percent of patients.12 Design of these studies differs from the current study, but collectively they document that brows ascend, or at the very least, remain level with advancing age in many individuals. Finally, it should be noted that cohort studies tend to reflect a population’s mean values; however, individuals, ethnicities, and opposite genders may have measurements that vary widely from the average. Thus, the current findings should not be interpreted to mean that eyebrows elevate in all individuals. In the longitudinal study by Lambros, brows descended in one-third of patients.12

Fig. 2. Box-plot representation of eyebrow height in young and older women. At each of the three positions, the brow is higher in older than in younger women. Relative position of the box plots in younger women shows an apex lateral shape to the brow, whereas in older women, the lateral brow appears flattened. Ascending horizontal lines of the box represent the 25th percentile, median, and 75th percentile of measured values. Vertical whisker lines extend to the smallest and largest observations.

The current findings also provide objective measurements about changes in eyebrow shape that occur with aging. In the 20- to 30-year-old cohort, the lateral brow was positioned significantly higher than the mid brow (Table 1).

Fig. 3. Brow shape changes from apex lateral [left) to apex neutral [right) slant. Typical results for patients from the 20- to 30-year-old [left) and 50- to 60-year-old [right) cohorts are shown. Younger patients have a medial brow that is low, with an apex lateral con-figuration. Older patients have an elevated medial and middle brow, which contributes to a flattened appearance. Measurements to the top of the brow margin are shown for each point measured.

The medial eyebrow was measured at the lowest height of any brow segment in either age group. These measurements describe the youthful eyebrow re-ported as the aesthetic ideal and serve as the goal for forehead rejuvenating procedures.214 In contrast, the 50- to 60-year-old patients have lateral and mid-brow segments at similar heights, creating a flat appearance or in some cases an apex medial configuration (Fig. 3). Although aging of the lateral brow is often referred to as ptosis, a more accurate term to describe the process is pseudoptosis, because the medial and middle brows ascend more than the lateral brow.

Multiple mechanisms may explain why brows paradoxically elevate with advancing age. “Spastic frontalis syndrome,†described by Ramirez, refers to chronic activation of the frontalis muscle with associated elevation of the brow/eyelid complex to overcome clinical or subclinical levator system weakness.1’’ This compensatory mechanism reportedly leads to a higher and more arched brow shape in people as they age. Further support for levator aponeurosis disinsertion was supplied by van den Bosch et al., who objectively documented that aging was associated with an elevated upper eyelid skin crease.11 An alternative explanation for brow elevation comes from the fact that patients chronically elevate their brows to reduce visual field obstruction from excess upper eyelid skin. Troilius noted that after blepharoplasty, the stimulus for frontalis contraction is alleviated, which in turn leads to eyebrow descent.5 In 10 patients who underwent upper blepharoplasty alone, he reported that brow height decreased postoperatively on average 3.3, 3.6, and 3.3 mm at the medial canthus, pupil, and lateral canthus, respectively. The author recommends careful analysis of brow position before blepharoplasty; otherwise, patients can appear worse postoperatively. A final hypothesis to consider is that eyebrows do not elevate with age, but rather the globe descends, creating an illusionary effect of pseudobrow elevation. Cohort studies refute this possibility by demonstrating that globe position in the supero- inferior axis does not change significantly in relation to periorbital soft-tissue structures such as the medial canthus” or bony orbit.16 Considered together, there are plausible mechanistic data to support brow elevation with aging.

Anatomical evidence for changes in brow position and shape with age are provided in detailed cadaver dissections by Knize.17 His study showed that beyond the temporal fusion line, where the frontalis muscle insertion ends laterally, there is no upward vector to counteract the gravitational forces on the soft-tissue temporal mass. The variable position of where the fusion plane terminates laterally provides an explanation for heterogeneity of lateral brow positioning among women. Finally, the presence of a lateral orbital retaining ligament between the superficial temporal fascia and the zygomaticofrontal suture fixes the lateral eyebrow, preventing movement to a degree equivalent to the medial brow. Tethering of the lateral brow with absence of frontalis in this area may explain why the lateral brow was not measured at significantly different heights in young and mature women (Table 1).

Data from this study objectively demonstrate that brows, in particular, the medial and mid-brow segments, elevate with age and explain why current brow-lift procedures, which tend to preferentially elevate the medial brow, create an unnatural appearance (Fig. 4).5-8-9 In addition, brow-lift operations often attenuate vertical glabellar furrows by manipulating the corrugator and procerus muscles.18 Weakening or removal of these muscles allows the medial brows to elevate and separate, with the brow starting in an aesthetically unfavorable position, lateral to the nasal ala.719 Based on these findings, a reappraisal of current brow-lift techniques is warranted to improve clinical outcomes.

Fig. 4. Typical stigmata after brow-lift surgery, including medial eyebrow ele¬vation, flat brow contour, and spread between medial brows. (Above) After brow-lift reversal, youthful brow morphology is restored, with a low medial eyebrow segment and an apex lateral arch shapeÂ

First, because there is heterogeneity in anatomy and how brows age, a cookie-cutter approach to brow rejuvenation should be abandoned, with operations tailored on the basis of preoperative findings and patient preference. Most patients require brow reshaping by restoration of the brow apex to above the lateral limbus of the iris. This suggests, in most instances, preferential elevation of the lateral brow, minimal or no elevation of the medial brow, and no manipulation of the glabellar musculature. Persistent forehead and glabellar rhytides may subsequently be treated with botulinum toxin as needed.20,21 Finally, the effect of concomitant blepharoplasty, which tends to lower the brow by alleviating the need to elevate excess upper eyelid skin, needs to be considered.

Unlike other areas of the body where there is relative descent of soft tissues, there is, on average, paradoxical elevation of the eyebrow with aging in women. The apex lateral contour of the youthful brow is transformed into a flattened brow (apex neutral) over time. These findings explain why current brow-lift procedures fail to achieve the aesthetic ideal and provide a rationale for lowering previously surgically elevated brows. When aiming to rejuvenate the forehead region, a youthful brow contour is more likely to be achieved if it is repositioned strategically along its course rather than simply “elevated.â€

Michael J. Yaremchuk, M.D.

Division of’ Plastic Surgery Massachusetts General Hospital 55 Fruit Street Wang 435 Boston, Mass. 02114 myarcinchuk@partners.org

REFERENCES

1. Westmore M. Facial cosmetics in conjunction with surgery. Paper presented at the Aesthetic Plastic Surgical Society Meeting; May 1974; Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada.

2. Freund RM, Nolan WB III. Correlation between brow lift outcomes and aesthetic ideals for eyebrow height and shape in females. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1996;97:1343-1348.

3. SchreiberJE, Singh NK. Klatsky SA. Beauty lies in the “eye¬brow” of the beholder: A public survey of eyebrow aesthetics. Aesthetic Surg J. 2005;25:348-352.

4. Gunter JP, Antrobus SD. Aesthetic analysis of the eyebrows. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1997:99:1808-1816.

5. Troilius C. Subperiosteal brow lifts without Fixation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004; 114:1595-1603; discussion 1604-1605.

6. Troilius C. A comparison between subgaleal and subperios¬teal brow lifts. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1999;104:1079-1090; dis¬cussion 1091-1092.

7. Behmand RA, Guyuron B. Endoscopic forehead rejuvena¬tion: II. Long-term results. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006; 117:1137— 1143; discussion 1144.

8. Swift RW, Nolan WB, Aston SJ. et al. Endoscopic brow lift: Objective results after 1 year. Aesthetic Surg J. 1999:19:287- 292.

9. Yaremchuk MJ, O’Sullivan N, Benslimane F. Reversing brow lifts. Aesthetic Surg J. 2007;27:367-375.

10. Farkas I.G. Hrec/ko TA. Katie MJ. Craniofacial norms in North American Caucasians from birth to adulthood: Ap¬pendix A. In: Anthropometry of the Head and Pace. 2nd ed. New York: Raven Press; 1994:241-333.

11. van den Bosch WA, Leenders I, Mulder P. Topographic anatomy of the eyelids, and the effects of sex and age. BrJ Ophthalmol. 1999:83:347-352.

12. Cambi os V. Observations on periorbital and midface aging. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007;120:1367-1376; discussion 1377.

13. Goldstein SM, KatowitzJA. The male eyebrow: A topographic anatomic analysis. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005:21:285- 291.

14. Ellenbogen R. Transcoronal eyebrow lift with concomitant upper blepharoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1983;71:490-499.

15. Ramirez OM. Subperiosteal brow lifts without Fixation (Dis¬cussion). Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004; 114:1604-1605.

16. Darcy SJ, Miller TA, Goldberg RA. VillablancaJP, DemerJL, Rudkin DIE Magnetic resonance imaging characterization of orbital changes with age and associated contributions to lower eyelid prominence. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008; 122:921— 929; discussion 930-931.

17. Knize DM. An anatomically based study of the mechanism of eyebrow ptosis. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1996;97:1321-1333.

18. Elkwood A, Matarasso A, Rankin M, Elkowitz M, Godek CP. National plastic surgery survey: Brow lifting techniques and complications. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;108:2143-2150; dis¬cussion 2151-2152.

19. Daniel RK, Tirkanits B. Endoscopic forehead lift: An oper¬ative technique. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1996;98:1148-1157; dis¬cussion 1158.

20. Guyuron B. Huddleston SW. Aesthetic indications for hot- ulinum toxin injection. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1994;93:913-918.

21. Fagien S. Botox for the treatment of dynamic and hyperki¬netic facial lines and furrows: Adjunctive use in facial aes¬thetic surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1999;103:701-713.