Improving Periorbital Appearance in the “Morphologically Proneâ€

Patients with prominent eyes are predisposed to lower lid descent and rounding of the palpebral fissure. This deformity may be exaggerated and symptomatic after conventional lower blepharoplasty. Normalization of the periorbital appearance in “morphologically prone†patients involves three basic maneuvers. Augmenting the projection of the infraorbital rim with an alloplastic implant effectively changes the skeletal morphology, thereby providing support for the lower lid and midface soft tissues. Subperiosteal freeing and elevation of the lower lid and midface recruits soft tissues and allows lower lid repositioning. Lateral canthopexy restores palpebral fissure shape and provides additional lid support. The technique can be adapted for morphologically prone patients who are first seeking improvement in their periorbital appearance or for those whose lid malposition and round eye appearance have been exaggerated by previous lower blepharoplasty. This surgery has been effective treatment for 13 morphologically prone patients operated on over a 4-year period. (Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 114: 980, 2004.)

Patients with prominent eyes are predisposed to lower lid descent, which may be exaggerated and symptomatic after conventional blepharoplasty. Eye prominence results from a deficiency in skeletal support or an excess of orbital soft-tissue volume. Eye prominence correlates with a more inferior position of the lower lid (resulting in scleral show) and a more medial position of the lateral canthus.1 Descent of the lower lid increases the height of the palpebral fissure, while the more medial position of the lateral canthus decreases its width. Hence, patients with poorly projecting upper midface skeletons have “round eyes†as compared with the long, narrow eyes characteristic of young people with a normal periorbital morphology.2-4 Furthermore, in the skeletally deficient, the lack of infraorbital rim projection and cheek prominence often allows their lower lid fat compartments to be visible, giving them “early bags.â€

Patients with prominent eyes have long been recognized to develop symptomatic lower lid descent (with exaggeration of their “round eyesâ€) after conventional lower blepharoplasty. Rees and LaTrenta5 studied the influence of periorbital morphology in predicting the like-lihood of symptomatic lower lid malposition after lower blepharoplasty. They found that patients whose eyes were prominent, either because of maxillary hypoplasia or thyroid ophthalmopathy, had a high incidence of lid malposition and dry-eye symptoms after blepharoplasty. Patients with prominent eyes were therefore considered “morphologically prone†to developing symptomatic lid malposition after lower blepharoplasty. Later, Jelks and Jelks6 categorized globe-orbital rim relationships and the tendency for the development of lower lid malposition after blepharoplasty. On sagittal view, they placed a line or “vector†between the most anterior projection of the globe and the malar eminence and lid margin. A “positive vector†relationship exists when the most anterior projection of the globe is posterior to the lid margin and the malar eminence. A “neutral vector†relationship exists when the most anterior projection of the globe is in the same plane with the lower lid and the malar eminence. A “negative vector†relationship exists when the most anterior projection of the globe lies anterior to the lower  lid and the malar eminence. They warned that patients whose orbital morphology has a negative vector relationship are prone to lid malposition after lower blepharoplasty. Recently, Hirmand et al.1 recommended the preoperative use of Hertel exophthalmometry as a more accurate preoperative screening method to identify eye prominence before blepharoplasty. All of these authors1,5,6 advocate altering surgical techniques to provide lower lid support when performing lower lid blepharoplasty in patients with prominent eyes. The treatment of postblepharoplasty round eyes in the morphologically prone has received little attention in the literature.

In his textbook, McCord7 proposed the loosening of the lower lid margin with a full-thickness transverse blepharotomy, canthotomy, and a small spacer graft with supraplacement of the lateral canthus in postblepharoplasty patients with lower lid retraction who have very prominent eyes. This type of procedure was originally used in patients with Graves disease. In a more recent review article,8 he demonstrated the use of spacer grafts combined with midface lifting (to vertically recruit cheek tissues instead of transverse blepharotomy) and periosteal strip canthoplasty (or fascia grafts). Baylis et al.9 stated that patients with prominent eyes frequently require the use of spacers for the correction of lower eyelid retraction. For patients with marked proptosis, they suggested considering (without documenting) orbital decompression or orbital rim onlay advancement in addition to soft-tissue repositioning.

This article presents a strategy for normalizing the periorbital appearance in morphologically prone patients. It can be adapted for morphologically prone patients who are first seeking improvement in their periorbital appearance or for those whose lid malposition and round eye appearance have been exaggerated by previous lower blepharoplasty. It utilizes alloplastic implants to augment the projection of the infraorbital rim,10 thereby effectively reversing the negative vector.4,10 This alloplastic skeletal augmentation is combined with subperiosteal composite midface and lower lid elevation as well as secure “bridge-of-bone†lateral canthopexy.4,11,12 It is adapted from experience with secondary reconstruction of the posttraumatic orbit,13-15 for patients with Graves ophthalmopathy, and for the treatment of postblepharoplasty lower lid retraction.4 This surgery has been effective treatment for 13 morphologically prone patients operated on over a 4-year period.

OPERATIVE STRATEGY

Overview

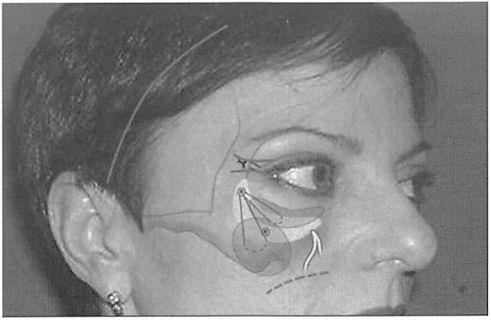

This procedure involves three basic maneuvers. Subperiosteal freeing and elevation of the lower lid and midface recruits lid tissues and allows lower lid repositioning. Augmentation of the infraorbital rim with an alloplastic implant effectively changes the facial skeletal morphology, thereby providing support for the lower lid and midface soft tissues. Lateral canthopexy restores palpebral fissure shape and provides additional lower lid support (Fig. 1, below).

Periorbital Access

Various combinations of incisions may be used to expose the infraorbital rim while mobilizing adjacent lid and midface soft tissues. My preference is to combine the lateral extent of the lower lid blepharoplasty with a gingival buccal sulcus incision. A transconjunctival and retroseptal incision may be added to improve exposure. If necessary, this transconjunctival incision can be connected with the lateral blepharoplasty transcutaneous incision with a lateral canthotomy. These additional incisions prolong palpebral edema and risk canthal distortion, respectively. Approaches that delaminate and relaminate the lower lid are avoided.

Midface Soft Tissue and Lower Lid Mobilization

Through a temporal (or bicoronal) incision, the lateral orbital soft tissues are mobilized. The superficial layer of the deep temporal fascia is incised at the level of the zygomatic frontal suture to expose the superficial temporal fat pad.16 This dissection is carried inferiorly until it reaches the zygomatic arch and lateral orbital rim previously exposed through the lateral blepharoplasty incision. Using the intraoral incision, the midface soft tissues are separated from the underlying skeleton and masseter muscle. This allows “en bloc†elevation of the malar midface and lower lid.4

Implant Placement

Porous polyethylene implants (Porex Surgical, Newnan, Ga.) have been specifically designed to augment the infraorbital rim area.10 They are always custom-carved to meet the specific needs of the patient. Approximately 3 to 5Â mm of augmentation at the infraorbital rim has been used. All implants are fixed to the skeleton with titanium screws (Synthes Corporation, Paoli, Pa.).

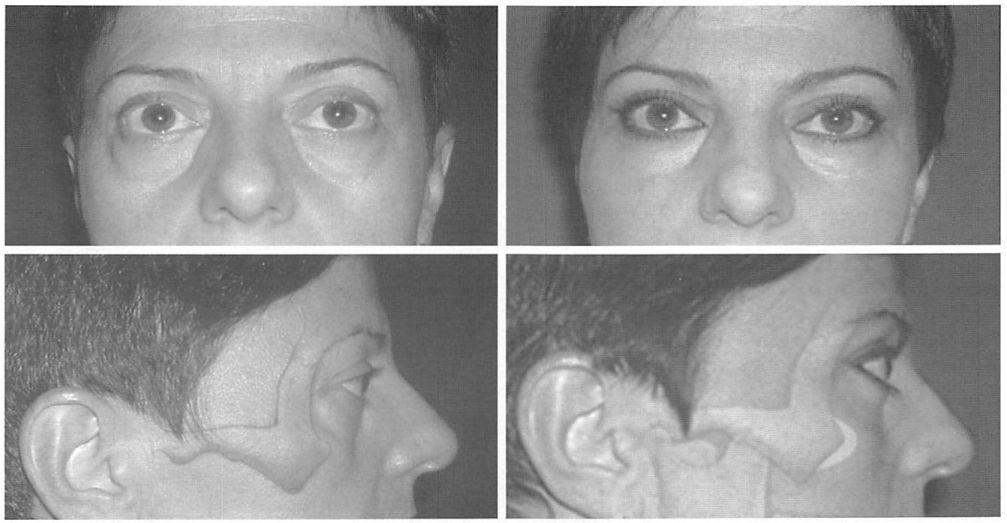

Figure1. I. A 49-year-old woman with prominent eyes and midface skeletal deficiency who had not previously been operated on underwent surgery to correct the “round eye†appearance. Preoperative frontal {above, left) and lateral views {center, left), with artist’s rendition of underlying facial skeleton. One-year postoperative frontal {above, right) and lateral views {center, right), with artist’s rendition of augmented facial skeleton. The infraorbital implant did not extend sufficiently medial to correct the tear trough deformity. No fat was removed from the lower lids. {Below) The operation: Cutaneous incisions {solid lines) indicate temporal and lateral extent of upper and lower lid blepharoplasty incisions. An intraoral incision {broken line) is used to access the midface skeleton. The lower lid, midface, and temporal soft tissues are freed by subperiosteal dissection. An implant augments the projection of the infraorbital rim area and is immobilized with screws. The midface soft tissues are resuspended using sutures tied to a screw in the lateral aspect of the infraorbital rim. The lateral canthopexy is performed by purchasing the lateral canthus with a figure-of-8 suture of 30-gauge wire, which is passed from within the orbit through drill holes placed in the lateral orbital rim and tied over the resultant bridge of bone.

Screw fixation of the implant prevents its perioperative displacement. Fixing the implant with screws also allows any gaps between the implant and the skeleton to be obliterated, thereby avoiding an unanticipated increase in augmentation in the area of the gaps. Finally, a rigidly immobilized implant can be tailored with a scalpel, high-speed burr, or rasp to provide the desired contour and an imperceptible implant-skeleton transition. Midface Elevation and Fixation Sutures are used to elevate and secure the malar midface and lid soft tissues. Through the intraoral incision, figure-of-8 sutures of 2-0 polyglycolic acid are used to purchase the suborbicularis oculi fat, malar fat pad, and underlying incised periosteum. A suture placed at the midpupil level is passed to the lateral lower lid incision, where it is tied to a screw placed in the lateral third of the reconstructed orbital rim. If a transconjunctival incision has been used, a screw placed in the midpupillary axis can provide the post for this suture. Another suture is placed in the lateral aspect of the malar fat pad (placed approximately 3 cm beneath the lateral canthus) and is tied to the screw in the reconstructed lateral orbital rim. After the sutures are tied around the screw, the screw is tightened until the head of the screw is flush with the bone or implant surface. The elevated suborbicularis oculi fat now rests on the augmented skeleton and helps to support the freed and elevated lid margin.

Lateral Canthopexy

A lateral canthopexy is performed to narrow the palpebral fissure and to provide additional support for the elevated lower lid margin. Through the lateral extent of the lower blepharoplasty incision, both limbs of the lateral canthus are purchased with a figure-of-8 30- gauge or 32-gauge wire suture. In the post-blepharoplasty patient, if scarring limits the upward mobility of the lateral canthus, the lateral third of the middle lamellae is incised with the needle tip electrocautery device. Through coronal access or, if the temporal incision is used, through the lateral extent of an upper lid blepharoplasty incision, two drill holes are placed in the lateral orbital rim 2 to 3 mm below the zygomaticofrontal suture. Each end of the wire is then passed from within the orbit through the drill holes to the lateral orbital rim. The wires are then twisted to one another over the bridge of bone between the two holes.4,11,12 Drill hole placement determines the lateral canthal position, which should be 2 to 3 mm above the medial canthal plane. The lateral canthus is not supraplaced.

Temporal Soft-Tissue Elevation

The temporal soft tissues are elevated and redistributed to avoid the Madame Butterfly look.17 If a coronal incision is used, a lateral brow lift will avoid any upper lid bunching after lateral canthal elevation. If the latter extent of an upper lid blepharoplasty is used, a small ellipse of skin is removed at its closure.

A suction drain is placed through a stab wound incision in the temporal scalp and beneath the composite lid-midface flap. Compressive dressings are not used because they direct fluid toward the more distensible lid soft tissues.

CLINICAL EXPERIENCE

Fourteen patients underwent this procedure over a 4-year period (eight men and six women; average age, 43 years; age range, 25 to 59 years). It has been effective in 13 patients; one patient thought he looked too different and requested implant removal 2 weeks after surgery. Prominent eyes were due to the deficient skeletal morphology in 12 patients and to thyroid ophthalmopathy in two patients. Seven patients (one with thyroid disease) had had previous lower blepharoplasty. Previous lower blepharoplasty patients, the other Graves patient, and one previously unoperated skeletally deficient patient had “dry eyes†and were relieved of their symptoms with this surgery. Two patients underwent revision canthoplasty and one patient had an overly prominent implant recontoured. Clinical examples are presented in Figures 1 through 4.

DISCUSSION

Infraorbital augmentation with screw-fixed porous implants normalizes sagittal globe-rim relations and provides support for midface and lid tissues. To effectively reverse the negative vector of the morphologically prone patient, an implant must increase anterior projection of the infraorbital rim. Tear trough and malar implants per se do not accomplish this unless they are modified to include the infraorbital rim. Skeletal augmentation is preferred over osteotomy unless the midface retrusion is accompanied by an occlusal disharmony that would also be corrected by skeletal advancement. Skeletal augmentation with alloplastic materials avoids the unpredictability accompanying the revascularization and subsequent remodeling associated with autogenous materials.18

Fig. 2. A 52-year-old woman had undergone bilateral upper and lower lid blepharoplasty 5 years before presentation. In addition to infraorbital rim augmentation, midface elevation, and lateral canthopexy, a paranasal augmentation was also performed. Dry-eye symptoms were resolved with surgery. (Left) Preoperative frontal and lateral views. (Right) Eighteen-month postoperative frontal and lateral views.

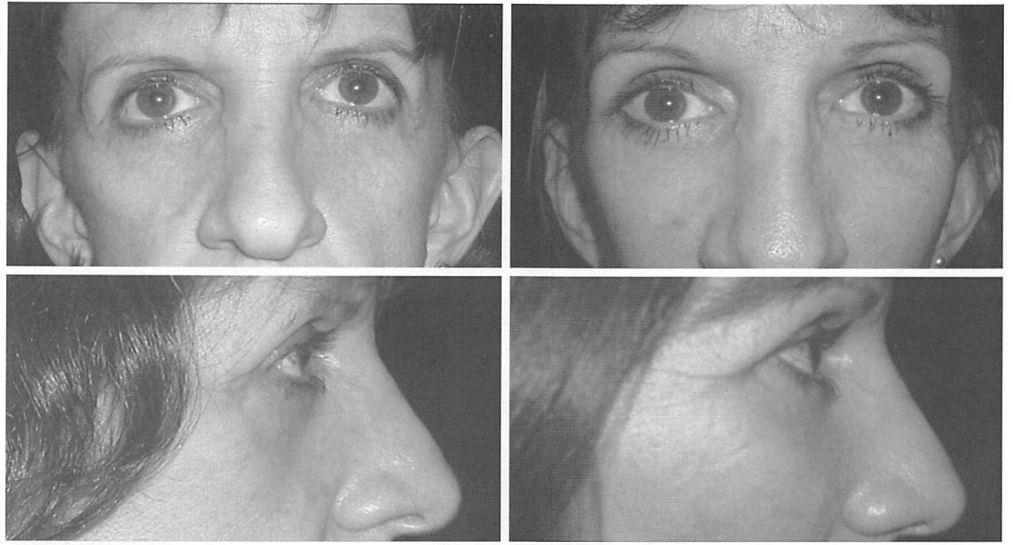

Fig. 3. A 52-year-old woman with a history of Graves disease had undergone blepharoplasty, two attempts at canthopexy, and rhytidectomy. An infraorbital rim augmentation, midface lift, and lateral canthopexy resolved dry-eye symptoms. (Left) Preoperative frontal and lateral views. (Right) One-year postoperative frontal and lateral views.

Porous polyethylene implants are used to augment the skeleton because their pore size (range, 160 to 368 jum; average, 240 /mm)19 allows soft-tissue ingrowth and relative “host incorporation†as opposed to the “host encapsulation†observed with smooth implants. The soft-tissue capsule that forms around porous polyethylene implants is not clinically detectable. Smooth implant capsules are often clinically apparent and can be distorting, particularly under thin skin. Soft tissues tend to adhere to the rough surface of porous polyethylene implants (like Velcro), requiring more extensive soft-tissue freeing for their positioning than do smooth implants. Since wide subperiosteal freeing is fundamental to this operation,the soft-tissue adherence characteristic of this implant is less detracting in this clinical application.

Figure. 4. A 30-year-old woman with Graves disease underwent medial and lateral orbital decompression with preservation of the lateral orbital rim. The orbital floor was not manipulated to avoid problems with globe displacement and possible diplopia. Globe-rim relations were further improved by augmenting the infraorbital rim, elevating the midface soft tissues, and performing lateral canthopexy. In this patient, a transconjunctival incision with lateral canthotomy was used. Note the distortion in the lateral canthal appearance on the right side due to improper lateral canthal realignment. Dry-eye symptoms were relieved. (Left) Preoperative frontal and lateral views. (Right) One-year postoperative frontal and lateral views.

Titanium screws are used in two aspects of this operation. Screws placed in the lateral orbit provide a post to which the midface suspension sutures can be tied. This allows secure midface soft-tissue elevation and repositioning, which is critical to the success of this procedure. Titanium screws are also used to fix the implant to the skeleton. Screw fixation prevents any movement of the implants, therefore assuring precise implant positioning. It also applies the implant to the skeleton, preventing any gaps. Gaps between the implant and the skeleton effectively, and unpredictably, increase the amount of augmentation. Finally, screw fixation allows the implant to be contoured “in place,†assuring precise contours and an imperceptible transition between the implant and native skeleton. Elevation of midface soft tissues using a translamellar approach with lateral canthoplasty was popularized by Shorr and Fallor’s “Madame Butterfly†operation17 to restore lower lid position after previous lower blepharoplasty. Hester et al.2″ modified this procedure to improve midface and lid contour as a primary aesthetic procedure. This surgeon adopted Phillips et al.’s1’ technique of subperiosteal midface soft-tissue repositioning for use after extensive facial skeletal degloving and reconstruction to restore a youthful cheek-lid interface during rhytidectomy.3 This adaptation avoided delamination and relamination of lid structures as well as violation of the lateral canthus—maneuvers that predispose to lid and canthal distortions. When combined with secure lateral canthopexy, en bloc subperiosteal midface and lower lid elevation through remote incisions has been effective in restoring lower lid position and palpebral fissure shape in patients presenting with lid distortion after previous lower blepharoplasty.1 This concept and similar techniques have been adapted by Hester et al.21 to decrease lid-related morbidity accompanying primary midface and lower lid rejuvenation procedures. These surgeons now limit the amount of interlamellar manipulation and often separate the lid structures from the facial skeleton through a lateral lid incision as described here.

The bridge-of-bone canthopexy is preferred for both conceptual and practical reasons. It can avoid the problems associated with canthoplasty which Fagien24 recently pointed out. He commented that canthoplasty can “pose a host of additional problems, including but not limited to long-term horizontal shortening, canthal asymmetry, dystopia, and dysjunction.†Unlike canthoplasty procedures, which disassemble and reassemble the lateral canthus and therefore, by design, alter the shape of the palpebral fissure, lateral canthopexy has the potential to restore palpebral fissure shape, including the lateral canthal angle. Drill holes placed in the lateral orbital rim can be placed after precise measurement, allowing for predictable and symmetric lateral canthal positioning. The bridge of bone provides a secure fixation point. The passing of the canthopexy wires from inside the orbit to outside applies the lid to the globe, thereby avoiding lid globe dysjunction in the lateral commissure when canthopexy sutures are tied to the outer surface of the lateral orbit. Furthermore, since the operation described here both elevates the lid and augments the patient’s skeleton, the need for canthal supraplacement to prevent bow stringing17 is avoided.

The stainless steel wire used for canthopexy has the potential to distort future magnetic resonance and computed tomography images.22,23 To avoid this problem, a canthopexy stitch of titanium wire (which has little effect on imaging) has been designed and should be available for general use in the summer of 2004 (Synthes Corporation, Paoli, Pa.).

REFERENCES

1. Hirmand, H., Codner, M. A., McCord, C. D., Hester, T. R., and Nahai, F. Prominent eye: Operative management in lower lid and midface rejuvenation and the morphologic classification system. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 110: 620, 2002.

2. Farkas, L. G., Hreczko, T. A., and Katie, M. J. Craniofacial norms in North America Caucasians from birth (one year to adulthood). In L. G. Farkas (Ed.), Anthropometry of the Head and Face, 2nd Ed. New York: Raven Press, 1994. Appendix A.

3. Yaremchuk, M. J. Subperiosteal and full-thickness skin rhytidectomy. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 107: 1045, 2001.

4. Yaremchuk, M. J. Restoring palpebral fissure shape after previous lower blepharoplasty. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. Ill: 441, 2003.

5. Rees, T. D., and LaTrenta, G. S. The role of the Schirmer’s test and orbital morphology in predicting dry-eye syndrome after blepharoplasty. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 82: 619, 1988.

6. Jelks, G. W., andjelks, E. B. The influence of orbital and eyelid anatomy on the palpebral aperture. Clin. Plast. Surg. 18: 193, 1991.

7. McCord, C. D., Jr. Eyelid Surgery: Principles and Techniques, 1st Ed. Philadelphia, Pa.: Lippincott-Raven, 1995. P. 95.

8. McCord, C. D., Jr. The correction of lower lid malposition following lower blepharoplasty. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 103: 1036, 1999.

9. Baylis, H. I., Goldberg, R. A., and Groth, M. J. Complications of lower blepharoplasty. In A. M. Putterman (Ed.), Cosmetic OculoplaslicSurgery:Eyelid, Forehead, and Facial Techniques, 3rd Ed. Philadelphia, Pa.: Saunders, 1999. P. 446.

10. Yaremchuk, M. J. Infraorbital rim augmentation. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 107: 1585, 2001.

11. Whitaker, L. A. Selective alterations of palpebral fissure form by lateral canthopexy. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 74: 611, 1984.

12. Flowers, R. S. Canthopexy as a routine blepharoplasty component. Clin. Plast. Surg. 20: 351, 1993.

13. Yaremchuk, M.J., and Kim, W. K. Soft-tissue alterations with acute, extended open reduction and internal fixation of orbital fractures./ Craniofac. Surg. 3: 134, 1992.

14. Yaremchuk, M. J. Orbital deformity after craniofacial fracture repair: Avoidance and treatment. /. Craniomaxillofac. Trauma 5: 7, 1999.

15. Phillips, J. H., Gruss, J. S., Wells, M. D., and Challet, A. Periosteal suspension of the lower eyelid and cheek following subciliary exposure of facial fractures. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 88: 145, 1991.

16. Stuzin, J. M., Wagstrom, L., Kawamoto, H. K., and Wolfe, S. A. Anatomy of the frontal branch of the facial nerve: The significance of the temporal fat pad. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 83: 265, 1989.

17. Shorr, N., and Fallor, M. K. “Madame Butterfly†procedure: Combined cheek and lateral canthus suspension procedure for post-blepharoplasty, “round eye,†and lower eyelid retraction. Ophthal. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 1: 229, 1985.

18. Chen, N. T., Glowacki.J., Bucky, L. P., Hong, H. Z., Kim, W. K., and Yaremchuk, M. J. The roles of revascularization and resorption on endurance of craniofacial onlay bone grafts in the rabbit. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 93: 714, 1994.

19. Shanbag, A., Friedman, H. L., Augustine, J., and Von Recum, A. F. Evaluation of porous polyethylene for external ear reconstruction. Ann. Plast. Surg. 24: 32, 1990.

20. Hester, T. R., Codner, M. A., and McCord, C. D. The “centrofacial†approach for correction of facial aging using the transblepharoplasty subperiosteal cheek lift.

21. Shorr, N., and Fallor, M. K. “Madame Butterfly†procedure: Combined cheek and lateral canthus suspension procedure for post-blepharoplasty, “round eye,†and lower eyelid retraction. Ophthal. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 1: 229, 1985.

22. Chen, N. T., Glowacki.J., Bucky, L. P., Hong, H. Z., Kim, W. K., and Yaremchuk, M. J. The roles of revascularization and resorption on endurance of craniofacial onlay bone grafts in the rabbit. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 93: 714, 1994.

23. Shanbag, A., Friedman, H. L., Augustine, J., and Von Recum, A. F. Evaluation of porous polyethylene for external ear reconstruction. Ann. Plast. Surg.

24: 32, 1990. 23. Hester, T. R., Codner, M. A., and McCord, C. D. The “centrofacial†approach for correction of facial aging using the transblepharoplasty subperiosteal cheek lift.