Masseter Muscle Reattachment After Mandibular Angle Surgery

BACKGROUND: Altering the dimensions of the mandibular angle by alloplastic augmentation or skeletal reduction requires elevation of the insertion of the masseter muscle, including the pterygomasseteric sling. Disruption of the pterygomasseteric sling during exposure of the inferior border of the mandible can cause the masseter muscle to retract superiorly, resulting in a loss of soft tissue volume over the angle of the mandible and a skeletonized appearance. Subsequent contraction of the masseter elevates the disinserted edge of the muscle and not only increases the skeletonized area, but also exaggerates the deficiency by causing a soft tissue bulge above it.

OBJECTIVE:

The authors describe the disinsertion of the masseter and the resulting deformity as a potential complication of mandibular angle surgery and review the technique for repair.

METHODS: The records of 60 patients (44 primary, 16 secondary) who presented for alloplastic mandible augmentation between 2003 and 2008 were reviewed.

RESULTS:

Nine patients presented with clinical signs of disruption of the pterygomasseteric sling after mandibular angle surgery. Five patients had clinical signs consistent with complete disruption. Two of these patients requested reconstruction. The other four had signs consistent with partial disruption. Through a Risdon approach, the masseter was successfully reinserted using drill holes placed at the inferior border of the mandible.

CONCLUSIONS:

Masseter disinsertion is a previously unreported sequelae after aesthetic surgery for the angle of the mandible. The resultant static and dynamic contour deformity can be corrected by reattaching the muscle to the inferior border of the mandible. (Aesthet SurgJ; 29:473-476.)

Aesthetic surgery of the mandibular angle includes both augmentation and reduction of the bony structure. Alloplastic augmentation can be performed to accentuate the definition of the lower jawline or to compensate for mandibular deficiency.1’8 Surgical reduction has also been described for the treatment of prominent mandibular angles, particularly in Asian societies.9 Unwanted outcomes from these procedures usually result from asymmetries, under corrections, or  over corrections. Both of these procedures (augmentation and reduction) require subperiosteal exposure of the skeleton with concomitant elevation of the masseter muscle insertion and the pterygomasseteric sling (PS). This exposure may disrupt the PS and cause the masseter muscle to retract superiorly, causing a loss of soft tissue volume over the mandibular angle and a skeletonized appearance.

SURGICAL ANATOMY

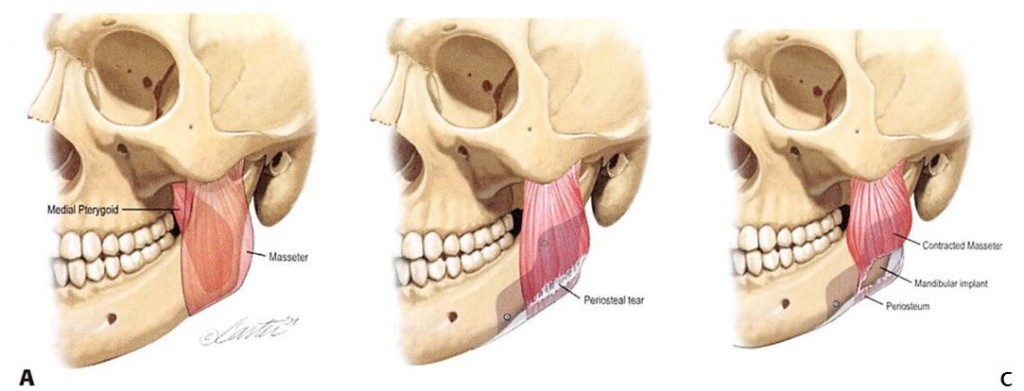

The masseter muscle originates from the inferior border and medial surface of the zygomatic arch and inserts broadly onto the lateral surface of the ramus of the mandible and the coronoid process. The medial pterygoid originates from the region of the lateral pterygoid plate and inserts onto the medial surface of the ramus10 (Figure 1, A). At the inferior border of the mandible, both the masseter and medial pterygoid muscles have strong tendinous insertions that adhere in proximity to the periosteum and, as a group, are often referred to as the PS. Again, disruption of the sling (Figure 1, B) can result in a loss of soft tissue. Subsequent contraction of the masseter elevates the disinserted edge of the muscle and not only increases the skeletonized area, but also exaggerates the deficiency by causing a soft tissue bulge above it (Figure 1, C).

Figure 1. An illustration of the pterygomasseteric sling (PS) and the effects after its disruption. A, At the inferior border of the mandible, both the masseter and medial pterygoid muscles have strong tendinous insertions that form the PS. B, The PS has been disrupted during exposure of the

inferior border of the mandible for placement of a mandibular angle implant. C, Contraction of the masseter elevates the disinserted edge of the muscle, resulting in a skeletonized area over the implant and a soft tissue bulge above it.

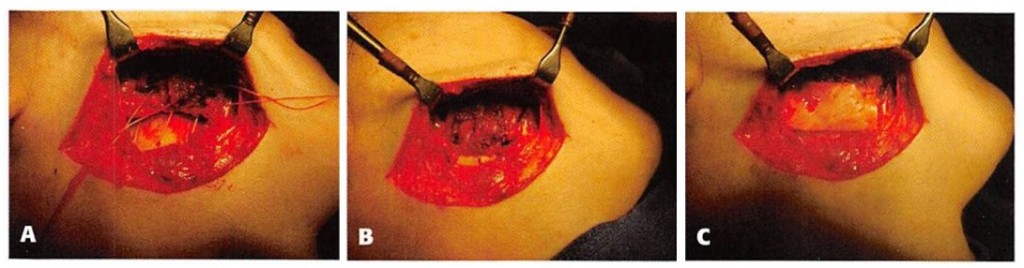

Figure 2. Intraoperative masseter reattachment. A, Through a Risdon incision just below the angle of the mandible, the edge of the masseter has been identified. Sutures have been placed through the inferior edge of the muscle and through drill holes in the inferior border of the mandible. B, The sutures have been tied down, bringing the masseter into a more anatomic position. C, A piece of Enduragen (porcine dermal collagen; Porex Surgical, Newnan, GA) has been sutured over the repair to ensure a smooth contour.

The PS and masseter insertion can be intentionally or unintentionally disrupted in a variety of surgical procedures that require exposure of the inferior border and angle of the mandible. By necessity, an extraoral approach to the angle of the mandible always requires the division of the PS.5 However, disruption of the sling can also occur through an intraoral approach. Standard intraoral techniques for exposure of the mandible use a variety of instruments that have been developed to facilitate the retraction and release of the masseter to gain surgical exposure to the inferior border of the mandible (including the Bauer retractor, the LeVasseur-Merrill retractor, and J-strippers).11 During split ramus osteotomy for mandibular advancement in orthognathic surgery, the exposure carried out along the buccal side of the mandible requires detachment of at least a portion of the masseter muscle.12 Elevation (but not disruption) of the PS has also been described in the subperiosteal placement of mandibular angle implants through an intraoral incision.1’3,5,6,13 Elevation of the PS is also necessary to expose the angle of the mandible for reduction surgery.9 Intentional incision of the PS has even been described as a means of increasing the vertical height of the posterior mandible.14

REATTACHMENT OF THE MASSETER MUSCLE

Reduction and augmentation of the posterior mandible are routinely performed from above through an intraoral sulcus approach. However, because masseter reattachment requires not only exposure of the inferior border of the mandible, but also mobilization of both the anterior and posterior surfaces of the masseter muscle, a more direct access to these structures is required. Therefore, under general anesthesia, the inferior border of the mandible is approached through a Risdon incision placed just below the angle of the mandible (Figure 2, A). The platysma is divided. Care should be taken to avoid injury to the marginal branch of the facial nerve or to the facial artery. After identifying the inferior border of the mandible, subperiosteal dissection of the anterior surface of the mandibular ramus is performed. This allows identification of the posterior surface and, subsequently, the detached inferior edge of the superiorly retracted masseter muscle. Drill holes are placed in the inferior border of the mandible. These are used to reattach the inferior edge of the masseter muscle with a nonabsorbable suture (Figure 2, B). If a mandibular angle implant is present, the muscle can be secured to the inferior edge of the implant. Additional implants may be required as an onlay to smooth residual contour irregularities (Figure 2, C).

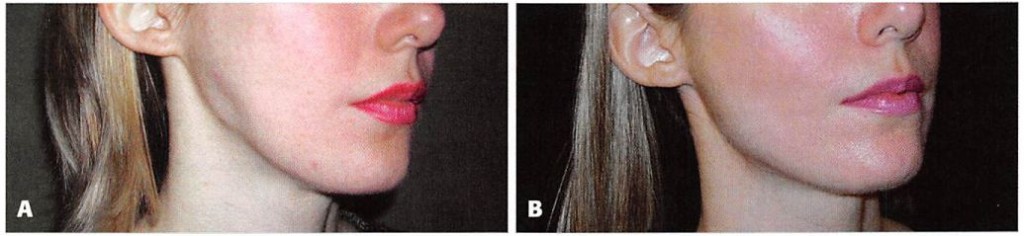

Figure 3. A, Preoperative view of the 30-year-old woman featured in Figure 2, who suffered disruption of the pterygomasseteric sling after unsatisfactory placement and subsequent removal of mandibular angle implants. Note the soft tissue deficiency in the region of the mandibular angle. The patient is pictured with active contraction of the masseter muscle, causing a superior bulge that exaggerates the soft tissue deficiency. B, One year after masseter reattachment, showing restoration of the contour of the mandibular angle.

Postoperatively, the patient is directed to employ an active range of jaw motion within 48 hours after surgery and to avoid forceful chewing for three weeks after surgery.

METHODS

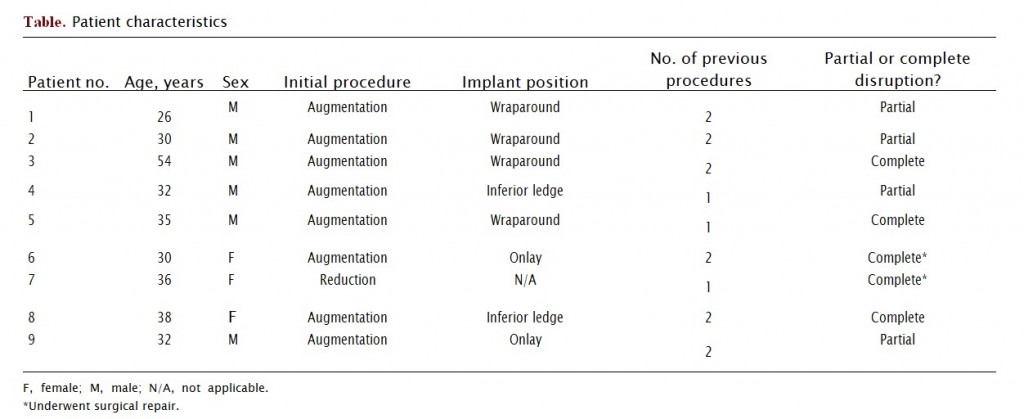

Between 2003 and 2008, 60 patients presented for alloplastic mandible angle augmentation. Forty-four patients underwent primary surgery with the senior author (MJY). This personal series constitutes 86 angles, with two patients undergoing unilateral surgery. Two of the patients (2.3%) were noted to have a slight soft tissue depression and overlying muscle bulge with forceful contraction of their masseter muscle after implant surgery. Of note, neither patient was aware of the subtle deformity. Sixteen additional patients were referred for revision of previous mandibular angle implant surgery. Seven of these patients complained of (and had clinical findings consistent with) masseter disinsertion. This resulted in a total of nine patients with this deformity (two primary patients and seven patients referred for revision). Five of the nine patients had clinical signs consistent with complete disruption of the PS. The clinical information associated with these patients is presented in the Table. Two of the patients with complete disruption requested surgical repair. The preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative images of one of the patients who underwent masseter reattachment are shown in Figures 2 and 3.

DISCUSSION

Surgery to alter the dimensions of the angle of the mandible requires elevation of the PS from the inferior border of the mandible. There have been previous reports discussing the complications specifically associated with mandibular angle augmentation or reduction.1 •3>4’9-15 The most common concerns include infection, hematoma, and asymmetry, although these appear to be relatively rare. Postoperative trismus is a more likely possibility when surgery involves resection of the masseter muscle.9 Other reported complications include temporary total facial nerve palsy, marginal mandibular palsy, mental nerve palsy, and retromandibular vein rupture.

Despite reports of other complications, neither the contour deformity that results if the sling has been disrupted during this exposure nor the surgical correction of the deformity have been reported. To our knowledge, the incidence of this problem after mandible angle surgery is not yet documented. In the series of 44 patients (86 mandibular angles) undergoing primary mandibular angle augmentation by the senior author (out of a total of 60 in the full series), two patients had evidence of partial disruption of their PS noted with forceful contraction of their masseter muscle. The incidence of partial disruption in this series was 2.3%.

A review of the clinical characteristics of the patients who presented with signs of damage to the PS provides a platform to discuss factors that may predispose to this condition (Table). The results from patients who suffered sling disruption after angle reduction suggest that sling elevation and retraction alone are sufficient to result in this deformity. This may reflect poor operative technique or may be a function of that patient’s particular anatomy. Most of these patients had more than one operation performed in the area. Repetitive surgery in this area, particularly the removal and replacement of implants, makes damage to the sling more likely. Many of the implants were designed to completely wrap around the inferior border of the mandible and therefore require degloving not only the anterior surface and inferior border of the mandible, but also its posterior aspect. Placing an implant with this design requires additional mobilization of the soft tissues, which may thereby increase the possibility of sling damage. The amount of vertical and lateral augmentation provided by the implant will also influence the potential for sling compromise.

It is possible that many, if not all, patients who undergo elevation of the PS have some disruption of its integrity that is not clinically appreciable. Even some of the subjects included in this study were unaware of the deformity. The subtle nature of this postoperative change is undoubtedly one reason why this sequela has not been previously documented.

Based on the personal experience of the senior author,13 we suggest the following practices to avoid PS disruption during mandible implant surgery:

1. Infiltration of the operative site with epinephrine- containing solution to maximize hemostasis;

2. Generous intraoral incisions to optimize operative site exposure and facilitate implant placement;

3. Strict subperiosteal dissection to minimize sling disruption;

4. Use of implants that provide lateral and vertical augmentation compatible with the patient’s soft tissue envelope; and

5. Screw fixation of the implant to prevent implant movement and lessen the likelihood of revisional surgery.

CONCLUSIONS

Elevation of the PS is required to expose the inferior border of the mandible during angle augmentation or reduction surgery. Disruption of the PS during exposure of the inferior border of the mandible can cause the masseter muscle to retract superiorly, with consequent loss of soft tissue volume over the angle of the mandible and a skeletonized appearance. This deformity is dynamic with contraction of the masseter, resulting in not only an increased area of skeletonization, but also an exaggeration of the deficiency because of a soft tissue bulge above it. Damage to the sling may be minimized by its careful elevation and retraction, the use of appropriately sized implants, and avoidance of secondary surgery. The clinical appearance may range from subtle to obvious, depending on the degree of disruption. This deformity can be corrected by reattachment of the muscle to the inferior border of the mandible. I

DISCLOSURES

The authors have no disclosures with respect to the contents of this article.

REFERENCES

1. Ousterhout DK. Mandibular angle augmentation and reduction. Clin Plast Surg 1991;18:153-161.

2. Yaremchuk MJ. Mandibular augmentation. Plast Reconstr Surg 2000;106:697-706.

3. Semergidis TG, Migliore SA, Sotereanos GC. Alloplastic augmentation of the mandibular angle. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1996;54:1417-1423.

4. Terino EO. Unique mandibular implants, including lateral and posterior angle implants. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am 1994;2:311-328.

5. Whitaker LA. Aesthetic augmentation of the posterior mandible. Plast Reconstr Surg 1991;87:268-275.

6. Aiache AE. Mandibular angle implants. Aesthetic Plast Surg 1992;16:349-354.

7. Taylor CO, Teenier TJ. Evaluation and augmentation of the mandibular angle region. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am 1994;3:329.

8. Ramirez OM. Mandibular matrix implant system: a method to restore skeletal support to the lower face. Plast Reconstr Surg 2000;106:176-189.

9. Baek SM, Kim SS, Bindiger A. The prominent mandibular angle: preoperative management, operative technique and results in 42 patients. Plast Reconstr Surg 1989:83:272-280.

10. Moore K, Dailey A. Clinically oriented anatomy, 4th ed. Baltimore: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 1999:921.

11. Ellis E, Zide MF. Surgical approaches to the facial skeleton, 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2006:155-161.

12. Reyneke JP. Essentials of orthognathic surgery. Chicago: Quintessence, 2003:248-249.

13. Yaremchuk MJ. Allas of facial implants. Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier, 2007:197-222.

14. Ferri J, Ricard D, Genay A. Posterior vertical deficiencies of the mandible: presentation of a new corrective technique and retrospective study of 21 cases. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2008;66:35-44.

15. Lee Y, Kim JH. Mandibular contouring: a surgical technique for the asymmetrical lower face. Plast Reconstr Surg 1999;104:1165-1171. Accepted for publication February 26, 2009. Reprint requests: Michael J. Yaremchuk. MD, Division of Plastic Surgery’, Department of Surgery, Massachusetts General Hospital, 15 Parkman St., Wang 435, Boston, MA 02114. E-mail: dr.y@dryaremchuk.com.

Copyright ® 2009 by The American Society for Aesthetic Plastic Surgery, Inc. 1090-820X/S36.00 doi: 10.1016/j.asj.2009.09.006