Health | Science

The Serious Side of

Plastic Surgery

After Surgery: Jennifer Davis got back her former appearance after eye surgery that reserved the effects of Graves Disease.

Long associated with the pursuit of vanity, cosmetic surgeons are finding new ways to help disease and accident victims look ‘normal’

By Raja Mishra, Globe Staff

One morning five years ago Jennifer Davis awoke to find her eye bulging out. She was at her mother’s house in Hingham. She rolled out of bed, walked to the bathroom, and casually glanced at the mirror

“It scared the hell out of me,” she said

Her eyelids were fully opened. Her eyes popped forward as if she’d just been mortally frightened or had glimpsed some impossible sight. She rubbed her face. The eyes refused to budge. She could scarcely fathom what was happening, not to mention what could possibly cause a person to slide into bed without a worry and awaken with a different face. Jennifer Davis could not see Jennifer Davis in the mirror..

“It changed my face completely. I was looking at a stranger.” Said Davis, now 32.

“I look at the plates I used in the early ‘90s and they almost look primitive,” said Dr. Ed Luce, chief of plastic surgery at university Hospital of Cleveland and president of the American Society of Plastic Surgeons.

These new tools, as well as many advances borrowed from cosmetic surgery, have made reconstructive surgeons increasingly able to deal with a variety of rare deformities that include Davis’s problem, disfigurement from World War II shrapnel and birth defects resulting from maternal drug use. No manual or textbook exists for these cases. They require a pastiche of new techniques and a healthy dose of improvisation.

After staring at the mirror in disbelief, Davis and her mother rushed to Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and got an answer: Graves’ disease. A defect in Davis’s immune system caused the production of an antibody that attacked the muscles around her eyes, causing them to swell overnight thus forcing her eyes out of their sockets. It was rare but not unheard of.

Before Surgery

Davis’s eyes took on an abnormal look because of swelling in the fat that lined her eye sockets.

Putting eyes in their Place

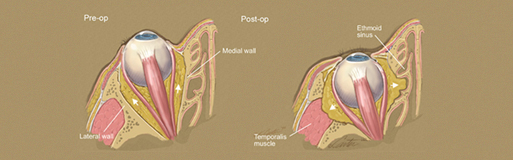

Graves Disease causes swelling in the intraorbital fat tissue that lines the eye socket, pressuring the eyeballs until they bulge out or even become paralyzed in extreme cases. But a new reconstructive surgery technique restores a normal appearance by widening the eye socket.

Grave’s Disease

Eyeball bulges out as intraorbital fat tissue

expands

Reconstructive surgery

The surgeon drills through two bones near the eye-the lateran wall and the medial wall- allowing the intraorbital fat to spread out from the socket, causing eyeball to recede

Denote interaorbital fat

Starting that day. Davis’s life would fall apart and her only hope of a normal existence would come from an unlikely place-plastic surgery.

Three weeks ago, the US Food and Drug Administration generated headlines by approving botox injections for temporary relief from the vertical frown lines that develop between the eyebrows with age. Month’s earlier, Fox News anchor Greta Van Susteren stimulated national chatter by undergoing botox treatment, then reappearing on air with a significantly altered look

But many plastic surgeons cringe at the popular impression they cater to the vanities of the rich. There is indeed a more serious side to the field reconstructive plastic surgery – that has made significant leaps in the past decade. Engineering advances have allowed reconstructive surgeons to use increasingly light and strong titanium plates and screws to repair deformities arising from bone problems.

New laser technology and surgical tools now allow them to remove even the most grotesque scars and tumors. Artificial cartilage and a variety of new implants have made post-mastectomy breast reconstruction once rare and complex, almost standard. The pace of improvement over the last decade, say the surgeons, has been steady.

Suddenly, it made sense. Davis for several years had had hyperthyroidism where an inherited defect in her immune system caused it to make antibodies that attacked and over stimulated her thyroid. A radio-iodine procedure a year before plus a daily prescription drug kept its symptoms weight loss dysfunctional leg muscles – in check.

The same immune system defect was causing her eyes to bulge said her doctors, a clear sign of Graves’ disease In fact, her hyperthyroidism,

they said was a product of Graves’ disease. One of every 1,000 people annually are diagnosed with it, mostly young or middle-aged women. There is no cure, though some of the symptoms can be alleviated with medication and treatment as Davis’s had been.

Her doctors, however said they could do nothing to stop her eyes from bulging. So, she walked out of the hospital and began the painful process of revealing her new deformity to the world.

First came her closest friend, her brother. “What happened?” he exclaimed.

Then came her boyfriend of two years. He refused to comment much on it, she remembered, saying that it would soon go away. She took that as a bad sign. Her colleagues at Provant Inc.. a Boston-based human resources consulting firm, were stunned then supportive though she often caught them staring.

But strangers were the worst.

‘I’d be sitting in a restaurant and people next to me would make some joke out loud about a deer caught in headlights, as if I couldn’t hear it, even though I was sitting right there,” she said “And little kids would point at me and ask, Mommy, what’s wrong with her?”

“Davis wore sunglasses whenever possible. After a year, her boyfriend left her.

“Everything around me fell apart,” she said.

Her life continued that way for two years. And then in summer 2000, Dr. Michael Yaremchuk called. The Massachusetts General Hospital plastic surgeon had actually seen Davis briefly two year ago but decided his abilities.

But now, be thought he could help. Graves’ Disease eye bulging lessens slightly after several years. Yaremchuck had determined that Davis’s condition was at a point where a rare plastic surgery procedure might help.

Yaremchuck, who also has a private cosmetic surgery practice, has special sympathy for patients like Davis. His text books are filled with photos of them. One patient accidentally drove his car underneath an 18-wheel rig. The entire left side of his face was shaved off, an omelet of misplaced facial structure and scar tissue. His “after” photo shows an almost-handsome man with only a single visible scar along his chin.

“People associate plastic surgery with Hollywood and face lifts” he said “They think it’s solely devoted to enhancement. But that’s only part of it.”

The current renaissance in reconstructive plastic surgery started in the late 1980s. Swiss orthopedic surgeons had started using steel plates to steady bone fractures allowing patients mobility.

Reconstructive surgeons saw an opportunity to treat a staple of their practice-jaws broken in first fights. They had long used wire to repair jaws. But wires often stretch disrupting jaw alignment.

“What plastic surgeons are really good as it taking technology from other fields” said Dr. Daniel Del Vecchio, a plastic surgeon at Tufts New England Medical Center, whose caseload is dominated by reconstructive cases.

Surgeons like Del Vecchio began taking postmedical-school courses on the new techniques, and by the early 1990s, plates and screws were the standard tools of the trade.

“The plates and screws have really made treatment of these patients easier.” Said Dr. Gregory A. Antoine, chief of plastic surgery at Boston Medical Center

Surgeons say there’s a clear difference between cosmetic and reconstructive cases.

“Both patients have self-gratification in mind but at different levels” said Antoine. “One is a Little more out of vanity and the other is really because of a major life change.”

Certainly, health insurers recognize the difference: They pay for reconstruction but not for most cosmetic work. Surgeons use a specific scale to draw a distinction between the two. The field has cataloged the size shape and placement of every facial structure for every ethnicity. Patients with feature two or less standard deviations or steps away, from the norm are cosmetic patients. But those in the third and fourth deviations are considered deformed. Davis fell in the third deviation. But the untrained eye can easily spot deformities..

“A deformity is basically whatever looks funny,” said Yaremchuk.

In September 2001, Davis checked into Mass. General Reconstructive surgery is usually a major medical procedure, and this was no exception Yaremchuk began with an incision above Davis’s right ear. He drew the scalpel up the side of her head, across the top of it and down to the other ear. Then he peeled her face down-standard during facelifts.

The goal was to widen her eye sockets. Using a high-speed electric drill, he burrowed cavities into the left and right walls of each eye socket, careful not to damage any part of the organs. The eyes began sinking back in.

Then he took two S-shaped hard plastic implants about the size of matches and nailed them to the top of her cheek bones, just below the eyes. This would make her cheek’s project.

Finally, he ripped each cheek mass from the skull. A tiny titanium screw was placed in each in each temple, just to the side of her eyes. Using sutures, Yaremchuk tied the cheek mass below to the screw above, anchoring the cheeks higher on Davis’ face.

He put her face back on, stitched close the head cut and seven hours later, it was done.

Davis’ eyes were stitched shut. She awoke to blackness and assumed a surgical mishap rendered her blind. A nurse calmed her. Four days later, the stitches came out. The hospital staff brought in a mirror.

“It was amazing,” she said.

Her face puffed with swelling. But it was her face.

“I kept wondering if my eyes were suddenly going to pop back open,” she said.

Her eyes were not as narrow as they once were. She looks like a woman with big eyes – but normally big eyes or, as surgeons might say, eyes less than two standard deviations from the average.

Davis’s eyesight remained perfect; the surgery was a complete success. It would take almost a year, however, to regain full feeling in her face. The only external scarring was on her scalp, and hair would soon cover it. The procedure in a sense cured her only remaining symptom of Graves’ disease.

“I viewed plastic surgery as a way to make someone 50 look 40,” she said. “I didn’t think they treated serious illness.”

She began dating again. Her confidence surged back. But there was always a voice, established during three years of shame, that asked; “It someone looking at me?”

“I just got over that a few weeks ago,” she said during a recent interview at a Waltham restaurant, seven months after her surgery.

During the three years Davis’s eyes bulged, she concluded Americans were overly judgmental and society was disgustingly superficial. In fact, when Yaremchuk told her the surgery would be possible, she considered passing on it. After all, she’d come to feel that external appearance was secondary. It seemed ironic to undergo such a severe medical ordeal in order to repair it. In the end, a single concern, shared by most reconstructive surgery patients, convinced her .

“I needed,” she said, “to fit back into society."