Bridge of Bone Canthopexy

Bridge of bone canthopexy has utility when significant movements of canthal position are required. It is a technique whereby the lateral canthal structures are purchased with a figure-of-eight suture of titanium wire. Drill holes are placed in the lateral orbital rim using the zygomaticofrontal sutures as reference landmarks. A canthal fixation point (the inferior drill hole) creates a measured distance from a fixed anatomic point (the zygomaticofrontal suture) assuring accurate and symmetric canthus positioning. Wire suture fixation over the bridge of bone created by the two drill holes provides maximum stability to counter soft tissue deforming forces. Fine adjustments can be made to the canthal position by twisting or untwisting the wire ends. (Aesthetic Surg J 2009;29:323-329.)

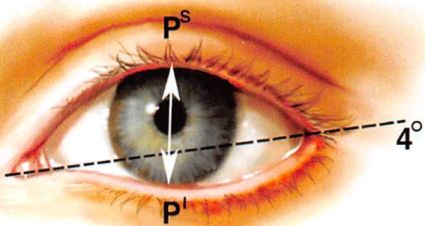

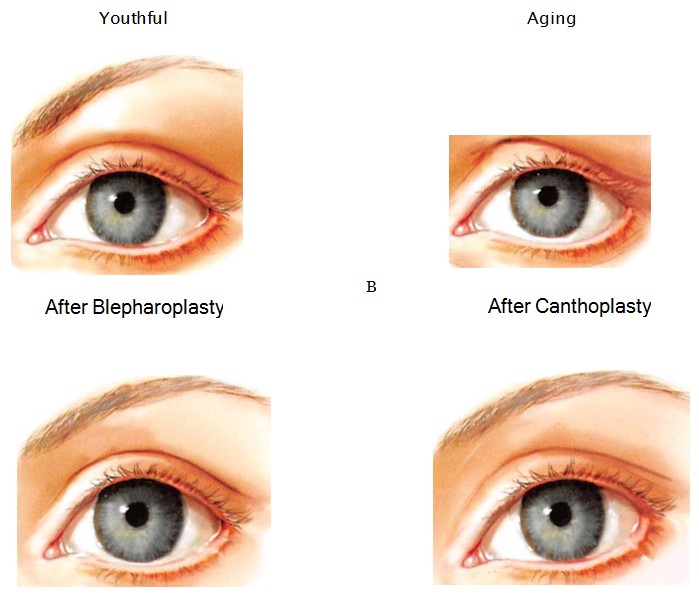

Youthful palpebral fissure are long and narrow, with a slight lateral upward inclination (Figure 1).

Distortions of or deviations from this shape may be secondary to heredity, aging, paralysis, trauma, or previous surgery.1 This distortion of shape inevitably manifests as rounding of the fissure, with inferomedial descent of the lateral canthus and concomitant descent of the lower lid margin. Lateral canthopexy, the surgical repositioning of the lateral canthus, is fundamental to altering or restoring the shape of the palpebral fissure.

ANATOMY OF THE LATERAL CANTHUS

Anatomically, the lateral canthus is more correctly termed a lateral retinaculum. The retinaculum receives contributions from the lateral horn of the levator aponeurosis, the lateral extension of the preseptal and pretarsal orbicularis oculi muscle (lateral canthal tendon), the inferior suspensory ligament of the globe (Lockwood’s ligament), and the check ligament of the lateral rectus muscle. It splits into anterior and posterior leaflets. The anterior leaf is contiguous with the orbital periosteum and the posterior leaflet inserts on the lateral orbital (Whitnall) tubercle. A change on the point of attachment or length of the retinaculum will cause significant changes in eyelid shape, tension, and coutour.2,3

HISTORY OF LOWER LID CANTHOPEXY

Lower eyelid tarsus suspension was originally described by Lexer and Eden4 in 1911, followed by Sheehan.5 Since then, many different techniques have been designed to restore lateral canthal position and correct lower eyelid malposition. Two requisites of lateral canthopexy make it technically challenging: symmetry and stability. Suturing of lateral canthal structures to similar points on the inner aspects of both lateral orbital rims can be difficult. Stable suture fixation can also be challenging, particularly when previous eyelid surgery has scarred and distorted periorbital tissues. Hinderer,6 Whitaker,7 Ortiz- Monasterio and Rodriguez,8 and Flowers9 reported techniques using drill holes made in the lateral orbital rim, which provided points of fixation that were both anatomically defined and secure.

In this article, we describe our technique of lateral canthopexy, an adaptation of the technique described by Whitaker.7 The lateral canthal structures are purchased with a figure-of-eight suture of titanium wire. Drill holes are placed in the lateral orbital rim using the zygomaticofrontal sutures as reference landmarks. This measured placement aids in achieving symmetric canthal repositioning.

Figure 1. Dimensions of the palpebral fissure as seen in a young white woman. The mean height of the palpebral fissure measured from the upper lid (Ps) to lower lid (P1) margin at the midpupil was 10.8 ± 1.2 mm (n = 200). The mean length of the eye fissure meas-ured from medial commissure to lateral commissure was 30.7 ± 1.2 mm (n = 200). The mean inclination of the eye fissure was 4.1° ± 2.2° (n = 50).’

The bridge of bone between the drill holes provides a stable platform over which the wire ends can be tied. Fine adjustments can be made to the canthal position by twisting or untwisting the wire ends.

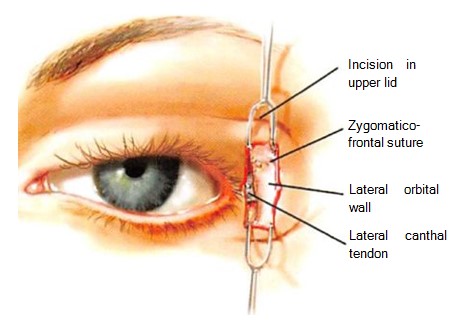

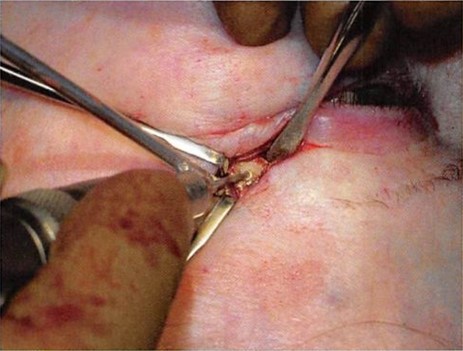

Figure 2. Through the lateral extent of the lower blepharoplasty incision, the lateral canthus is identified and is freed from Whitnall’s tubercle by subperiosteal dissection.

Figure 3. Through the lateral extent of an upper blepharoplasty incision, the zygomaticofrontal suture has been exposed.

SURGICAL TECHNIQUE

Overview

Bridge of bone canthopexy requires exposure of the lateral orbit and mobilization of the lateral canthus soft tissue mechanism. Its efficacy is based on the stable suture fixation point provided by drill holes placed in the bone of the lateral orbit. This procedure can be performed under local or general anesthesia.

Incisions

This procedure requires access to the lateral orbital rim from the level of Whitnall’s tubercle to the zygomaticofrontal suture. This can be accomplished through the lateral extent of an upper blepharoplasty incision. Most often, we prefer the lateral extent of both upper and lower blepharoplasty incisions because the lower blepharoplasty incision provides superior visualization of the lateral canthal tissues (Figures 2 and 3). This anatomy can also be approached from the access provided by a bicoronal incision if a concomitant brow lift is performed.

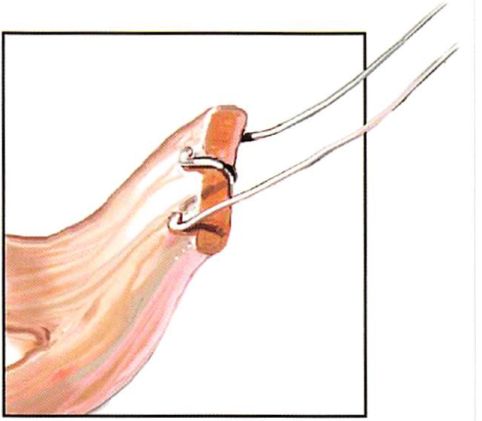

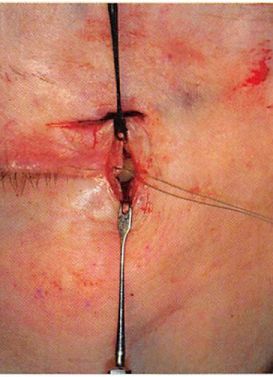

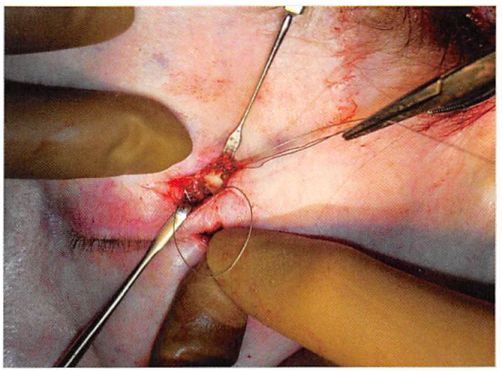

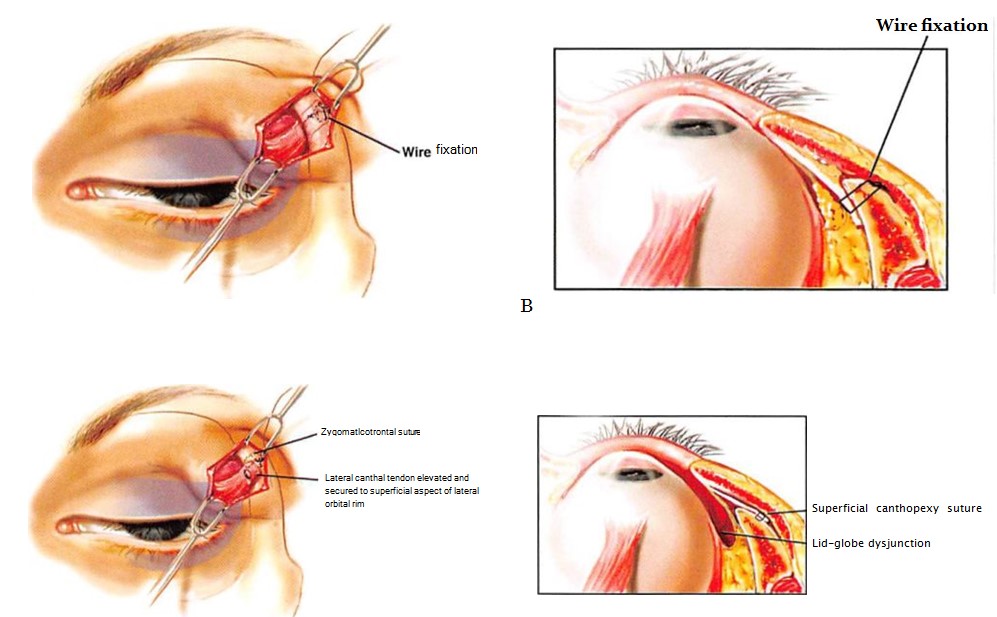

Figure 4. The lateral canthus is purchased by a figure-of-eight, 30- gauge titanium wire suture.

Figure 5. The lateral canthal mechanism being purchased with 30-gauge titanium wire suture.

Figure-of-Eight Suture

When only 1 or 2 mm of superior or lateral movements of the lateral canthus and adjacent lid margin are desired, one or both limbs of the lateral canthus may be purchased with a figure-of-eight suture without freeing the lateral retinacular structures from the lateral orbit (Figures 4 to 6). The amount of commissure movement will be limited by the length of the ligament, the point of suture purchase relative to the lateral commissure, and the position of the lateral orbit drill holes. This approach is most often appropriate when there is minimal commissure malposition and no local scarring from previous lid surgery.

When more significant movements of the lateral commissure and lid margin are desired, complete subperiosteal freeing of the lateral retinacular structures is required before figure-of-eight suture purchase of both limbs of the ligament. Through the lateral extent of the lower blepharoplasty incision, the lateral retinaculum is identified and dissected, and both limbs of the lateral canthus are purchased with a figure-of-eight 30- or 32- gauge titanium wire suture. If middle lamellar scarring from previous lower lid surgery restricts canthal movement, the lateral third of the middle lamellae is sufficiently incised with needle tip electrocautery to allow it to be freely mobile.

Figure 6. The lateral canthal mechanism has been secured with titanium wire.

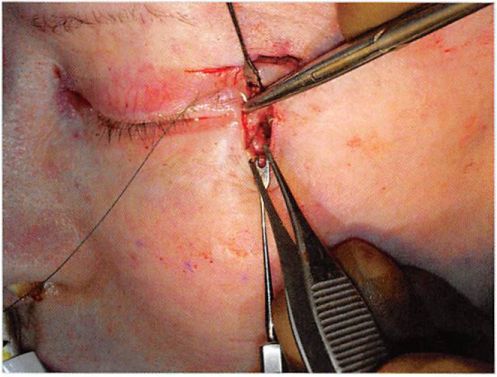

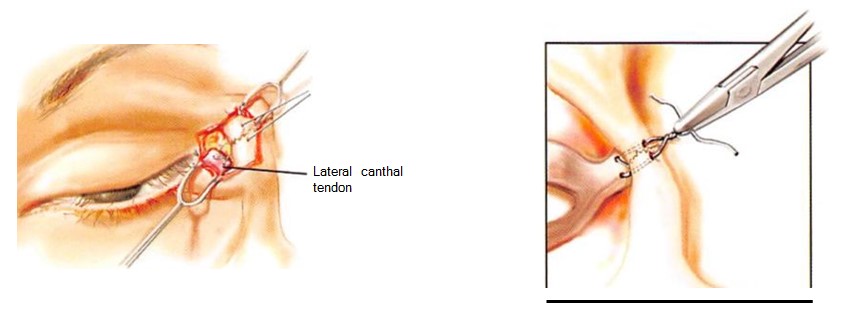

Figure 7. A drill hole is made in the lateral orbital rim at the zygomaticofrontal suture. The second drill hole will be made just below.

Drill Holes

Through the upper access approach, the zygomati cofrontal suture is identified. This suture provides a landmark to allow symmetric placement of drill holes made in the lateral orbital rim. Using the zygomatico- frontal suture as a landmark, two drill holes are placed in the lateral orbital rim. The position of the lower drill hole is important, because it determines the maximum upward movement of the canthus. The upper drill hole is necessary to create the bridge of bone, a stable fixation point (Figure 7).

Figure 8. One end of the canthopexy wire has been passed from inside the orbit to outside the orbit through the upper drill hole. The other end of the canthopexy wire is being threaded through a wire doubled on itself, which was passed from outside the orbit to within the orbit. This doubled wire creates an eyelet through which the other end of the canthopexy wire is threaded. Pulling the doubled wire will bring the canthopexy wire outside of the orbit.

The lateral canthal position and aperture shape are determined by the position of the drill holes, which should be 2 to 3 mm above the medial canthal plane in order to give the intercanthal axis a slight upward tilt. The drill holes should also be placed in the internal orbit about 3 to 4 mm posterior to the anterior margin of the lateral orbital rim, so that the lateral lid will not be drawn away from contact with the globe. To determine the ideal position of the drill holes, one can grasp the lateral canthus and tuck it against the lateral orbital rim until the desired canthal and lower lid position is obtained. The positions are marked and drill holes are then made at that point. Most often, they are positioned just at and 2 mm below the zygomaticofrontal suture. Each end of the wire is then passed from within the orbit and through the drill holes to the lateral orbital rim (Figures 8 and 9). The wires are then twisted together over the bridge of bone between the two holes (Figure 10). Wire twisting will determine canthal movement. The location of the lower drill hole dictates the limit of movement. The point of fixation of the lateral canthus relative to the lateral orbital rim determines the relation of the lower lid to the surface of the globe (Figure 11).

Figure 9. Each end of the wire suture is passed from within the orbit Figure 10. Wires are twisted sufficiently to position the lateral canthus. through drill holes made in the lateral orbital rim. The ends of the wire suture are twisted together over the bridge of bone. Passing the wire from inside to outside the orbit applies the lid to the globe.

The strand of twisted wire ends is left approximately 5 mm long. This length of twisted wire ends has two advantages. First, it allows intraoperative (or postoperative) adjustment of the canthal position by simply twisting or untwisting the wires, making it unnecessary to repeat the suturing process. Second, this length allows the ends to be placed into one of the drill holes or into the orbit. This maneuver avoids postoperative visibility or palpability of the wire ends (Figure 12). If local incisions are used for access, an ellipse of skin and muscle is removed from the lateral aspect of the upper lid in order to eliminate the lid redundancy caused by the upward movement of the canthus. The wounds are closed in layers.

Figure 11. The position of the lateral canthus relative to the lateral orbital rim determines the relation of the lower lid to the surface of the globe. A, The lateral canthopexy stitch is passed through the inner surface of the lateral orbital wall and tied on its outside surface. B, The axial view of part A shows that the lid is applied to the globe. C, The lateral canthopexy stitch is attached to the periosteum of the anterior surface of the lateral orbital rim. D, The axial view of part C shows a gap between the surface of the globe and the lateral aspect of the lower lid.

COMPLICATIONS AND OUTCOMES

When extensive dissection is performed, postoperative chemosis is common. In addition to ophthalmic lubricants, we have found that a temporary tarsorrhaphy stitch left for five to seven days significantly attenuates this process. The tarsorrhaphy is performed by placing a single 5-0 nylon suture through the upper and lower lid margins and adjacent skin. Tying the suture approximates the lids.

The potential “weak link†in the bridge of bone canthopexy is the point of wire attachment to the canthus. In our experience, revision surgery after bridge of bone canthopexy has been necessary after two clinical scenarios that may compromise this point of attachment. One of the scenarios that limits the procedure’s efficacy is when the integrity of the lateral canthus has been compromised, thereby undermining the purchase of the canthopexy suture.

Figure 12. The free end of the twisted wires will be shortened and positioned behind the lateral orbital rim to prevent their visibility and palpability.

This is not uncommon when a previous canthoplasty has been performed. The other situation leading to relapse is when the canthopexy is performed without achieving sufficient mobility of the canthal structures to passively place the canthus in the desired position. When a canthopexy is performed in the face of severe vertical lid deficiency, scar contraction forces will inevitably result in the canthopexy suture cutting through the purchased canthal soft tissues, with subsequent canthal descent.

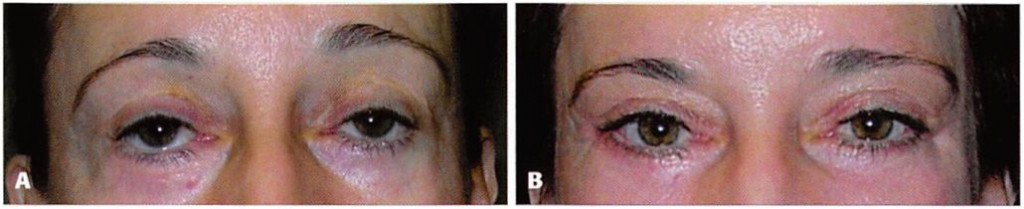

Clinical outcomes from the use of the bridge of bone canthopexy are shown in Figures 13 through 16.

CONCLUSIONS

The terminology of lateral canthal surgery is confusing. A lateral canthopexy repositions the lateral canthus. It moves the displaced or attenuated lateral canthal mechanism to a desired position with or without its disinsertion. Because it does not violate the lateral commissure or lower lid margin, it maintains (or has the potential to restore) palpebral fissure shape, including the lateral canthal angle. By design, canthoplasty procedures such as the lateral tarsal strip alter the shape of the palpebral fissure because they disrupt the lateral commissure while shortening the lower lid margin.10 Lateral canthal/horizontal eyelid shortening procedures were first developed to treat functional eyelid disorders. By decreasing the surface area of exposed cornea, they ameliorated symptoms of dry eyes. They were later adapted to aesthetic surgery as prophylaxis against or a correction for postblepharoplasty lid malposition. These lid margin shortening procedures are appropriate treatment for senile ectropion and entropion—situations where the lid margin is redundant. Their aesthetic implications should not be discounted. Canthoplasty procedures may be effective in elevating the lower lid, but they often exaggerate senile or postsurgical distortion of palpebral fissure shape (Figure 17).

Canthopexy procedures that reef or attach the lateral canthal tendon to the lateral orbit periosteum provide sufficient stability and accuracy as prophylaxis against and correction of mild postblepharoplasty lid malposition. Bridge of bone canthopexy has its greatest utility when significant movements of canthal position are required. A canthal fixation point (the inferior drill hole) created at a measured distance from a fixed anatomic point (the zygomaticofrontal suture) assures accurate and symmetric placement.

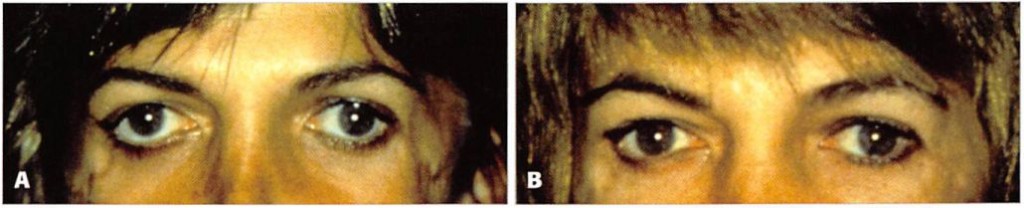

Figure 13. A, Preoperative view of a 35-year old woman with Treacher-Collins syndrome who underwent augmentation of her coloboma with custom-carved porous polyethylene implants and bridge of bone canthopexy. B, Two years after bridge of bone canthopexy.

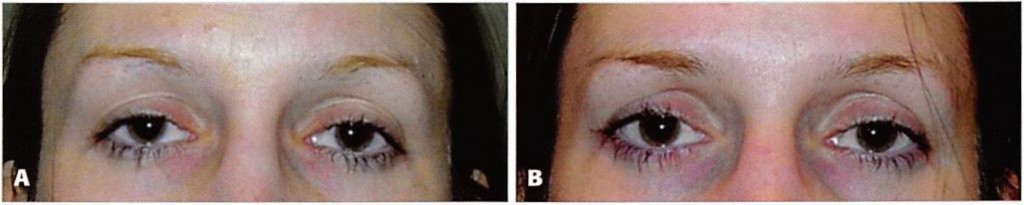

Figure 14. A, Preoperative view of a 27-year-old woman who desired upward movement of her lateral canthus. She had not undergone previous orbital surgery. B, Six months after bridge of bone canthopexy.

Figure 15. A, Preoperative view of a 50-year-old woman with previous lower lid blepharoplasty who underwent subperiosteal midface lift, infraorbital rim augmentation, and lateral canthopexy. B, One year after bridge of bone canthopexy.

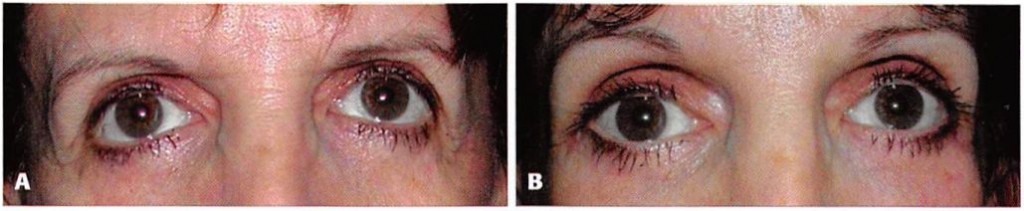

Figure 16. A, Preoperative view of a 52-year-old woman who had undergone a previous brow lift, rhytidectomy, and upper and lower lid blepharoplasty. Lower lid retraction was treated with multiple canthopexies, spacer grafts, and full-thickness skin grafts. Dry eye symptoms persisted. Infraorbital rim augmentation, midface lift, and lateral canthopexy resolved her symptoms. Her brows and hairline were repositioned. B, One year after bridge of bone canthopexy.

Figure 17. A, In young adults with normal skeletal morphology, the palpebral fissure is long and narrow. With aging (B), descent of the lower lid and medial migration of the lateral canthus rounds the shape of the palpebral fissure. Standard blepharoplasty techniques that remove lower lid skin (and often muscle) tend to lower the lower lid margin, further rounding the palpebral fissure (C). Canthoplasty procedures, by design, alter the shape of the palpebral fissure because they disassemble and reassemble the lateral canthus while shortening the lower lid margin (D). Because it does not violate the lid margin, lateral canthopexy maintains or has the potential to restore palpebral fissure shape, including the lateral canthal angle.

Wire suture fixation over the bridge of bone created by the two drill holes provides maximum stability to counter soft tissue-deforming forces. The senior author (MJY) uses this technique alone to reposition the lateral canthus and lower lid when the periorbital tissues are adequate. When postblepharoplasty tissues are inadequate, a subperiosteal midfacelift is added to recruit cheek and lid tissues.11 To provide support for lid and midface soft tissues, sagittal augmentation of the infraorbital rim is added to the lid and canthus repositioning algorithm in postblepharoplasty patients with midface skeletal deficiency (those who are “morphologically proneâ€).121

DISCLOSURES

The authors have no disclosures with respect to the contents of this article.

REFERENCES

1. Farkas LG, Hreczko TA. Kalic MJ. Craniofacial norms in North American Caucasians from birth (one year) to young adulthood. In: Farkas LG, editor. Anthropometry of the head and face. New York: Raven Press; 1994:241-235.

2. Gioia VM, Linberg JV, McCormick SA. The anatomy of the lateral canthal tendon. Arch Ophiluilmol 1987:105:529-532.

3. Most SP, Mobley SR. Larrabee Jr VVF. Anatomy of the eyelids. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am 2005:13:487-492.

4. Lexer E, Eden R. Uber die chirurgische Behandlung der peripheren Facialislahmung. Beitr Klin Chir 1911:73:116.

5. Sheehan JE. Plastic surgery of the orbit. New York: Macmillan; 1927.

6. Hinderer UT. Correction of weakness of the lower eyelid and lateral canthus. Personal Techniques. Clin I’last Sarg 1993:20:331-349.

7. Whitaker LA. Selective alteration of palpebral fissure form by lateral canthopexy. Plast Reconstr Surg 1984:74:611-619.

8. Ortiz-Monasterio F, Rodriguez A. Lateral canthoplasty to change the eye slant. Plast Reconstr Surg 1985:75:1-10.

9. Flowers RS. Advanced blepharoplasty: Principles of precision. Gonzalez-Ulloa M, Meyer R. Smith JW, editors. Aesthetic plastic surgery, vol 2. Padua, Italy: Piccin Nuova Libraria; 1987:115.

10. McCord CD. Boswell CB, Hester TR. Lateral canthal anchoring. Plast Reconstr Surg 2003;112:222-236.

11. Yaremchuk MJ. Restoring palpebral fissure shape after previous lower blepharoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg 2003;111:441-450.

12. Yaremchuk MJ. Improving periorbital appearance in the “morphologically prone.” Plast Reconstr Surg 2004;114:980-987.

Accepted for publication July 8. 2009.

Reprint requests: Michael J. Yaremchuk, MD, Massachusetts General Hospital, 15 Parkman St., Boston, MA, 02114. E-mail: dr.y@dryaremchuk.com.